If the surfing goes well, the medals could be presented as soon as July 30th.

These waves are created by a unique combination of fluid dynamics, geology and geometry that makes them as dangerous as they are beautiful and fascinating.

“If it was a ski run, it would be like a triple black diamond,” said former pro surfer Jessie Miley Dyer.

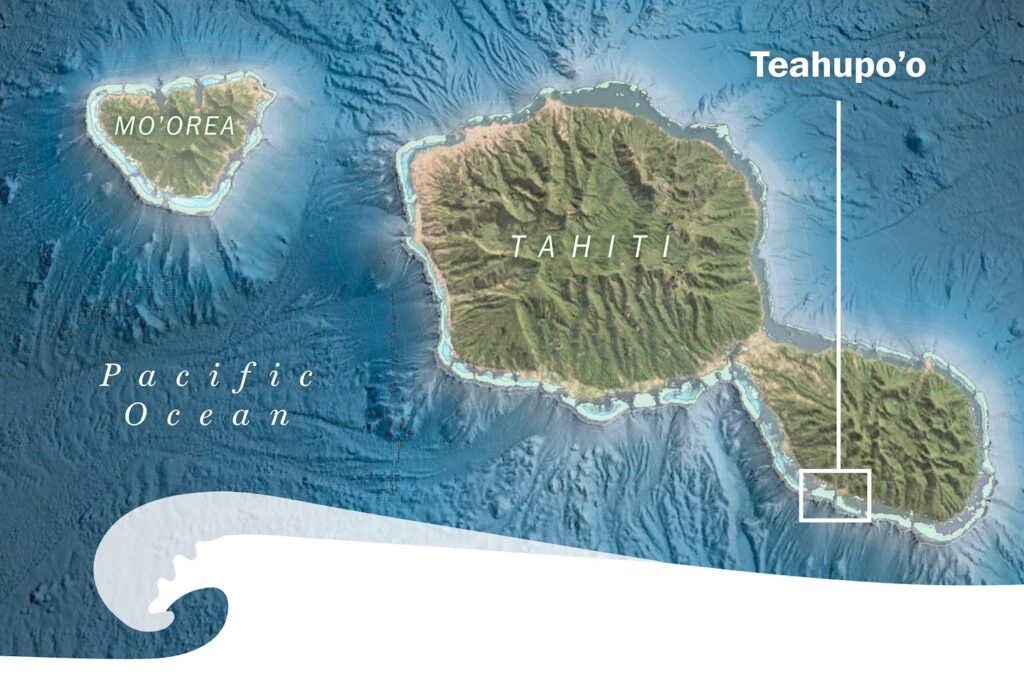

Teahupo is the name of both the wave and the town on land, and roughly translates to “Wall of Skulls” or “Broken Skulls.” Either way, you get the point.

In the 1980s and 1990s, it was considered too rough to surf, and at least five surfers were killed trying to ride the wave.

Surfers are calling it one of the world's “heaviest” waves, meaning it's dangerous but powerful, said World Surf League commissioner Myrie Dyer.

“It's a reef break, so you can hit the reef and it's pretty shallow in parts,” she said, “but the wave itself is so thick that it makes the waves bigger. So that's what gets a ton of water onto the reef.”

All this water comes from violent storms near Antarctica, thousands of miles away.

The storm unleashes a surge of water and energy that flows virtually unimpeded, roaring up the base of the dormant volcano that formed Tahiti and slamming into the surrounding coral reefs.

This almost instantaneous transition from deep to shallow water is what gives the wave its hollow shape and power, said Kevin Wallis, head of forecasting for Surfline, which provides Olympic forecasts and condition reports.

As the swell approaches, the water churns as it somersaults, drawing water away from the reef as the upper shelf of the wave collapses.

Willis said the wave height at Tiupo can vary from a few feet to 50 feet, but is usually between 6 and 15 feet, but because of special fluid dynamics, surfers surfing on the inside of the wave are actually below sea level, and the water below the wave's break is shallow.

The swimmers have little to no cushioning as they are slammed against the reef or dragged across the sharp coral surface.

If the reef were just a wall of coral, the wave would break all at once — surfers call it a closeout — and it wouldn't ride as well, Willis says. It wouldn't have the long, tapered curls.

But in one particular spot, it seems as if the streams that have been flowing there for thousands of years have decided to shape an ideal spot for surfing.

Coral can only grow in saltwater, so the reef formed at an angle that was out of reach of the freshwater flowing from the river mouth. The constant water flowing down from the mountains carves deep grooves into the soft volcanic rock.

So when a swell hits a particular groove in the reef, the water rises and folds over itself, forming a long, tapering barrel before dissipating.

“If you say to someone, 'OK, build a shape that will absorb the energy of the wave over the shortest possible distance,' that's exactly the angle the reef will grow at,” says surfing legend Laird Hamilton, who stunned surfers by conquering Choupo's giant waves in 2000.

“Literally all of the wave's energy is gone in one hit. That's why the wave rises up and forms a giant cylinder and then explodes, because it absorbs the energy of the wave and completely absorbs it within a few hundred feet.”

That means the nearby lagoon is a kind of sanctuary, Hamilton said: “You wouldn't even know there were waves out there.”

Miley Dyer said Choupo, with its shallow, clear water and towering mountain backdrop, is “one of the most visually surreal waves to surf,” but the waves are also so powerful that surfers can't just watch.

““You get to experience the most beautiful, clean waves in the world,” she said, “and at the same time it makes you really concentrate. You can't just mess around.”

Sally Jenkins and Adrienne Blanco Ramos contributed to this report.

Source: Bathymetry data from the French Hydrographic Office (SHOM), Surfline, satellite imagery ©2024 Maxar Technologies.