For the better part of its first 19 years, Poly Pavilion was best known as the place where history was made on the hardwood, but for one week in the summer of 1984, the floor of UCLA's famed sports arena was transformed into a glorious cacophony of mats, bars and beams.

Like John Wooden, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bill Walton before them, the 12 gymnasts who represented the United States at the Los Angeles Summer Olympics left their indelible mark on gymnastics here.

For six nights, the U.S. men's and women's Olympic gymnastics teams flipped, tumbled and vaulted to Olympic glory. They wowed sellout crowds, won 26 medals in total, 10 of them gold, and heralded the arrival of American gymnastics on the world stage.

Simone Biles changed gymnastics.Now we need to make it more accessible to kids of color.

Can't see the graphic? Click here to view it.

Night 1: Men's Team All-Around

July 31, 1984

When the U.S. men's gymnastics team entered Pauley Pavilion for the first time on the night of the team all-around final, they did so through a small tunnel connecting the venue to the warm-up gym a few hundred yards away.

In the tunnel, away from the gaze of thousands of spectators, the players huddled one last time before taking to the court. Tensions were running high. Outwardly they were high-fiving and encouraging each other, but deep down they had doubts. “We never dreamed we'd win the gold medal,” Bart Conner said. “We thought China was so strong, [didn’t] We didn't know if there was any way we could make this work.” Sensing the anxiety spreading throughout the team, coach Abby Grossfeld decided it was time for a unique pep talk. “Coach called us aside right before we were to go on the court,” Mitch Gaylord recalled. “And he said, 'Hey guys, I want you to remember that there's nothing to be nervous about here. There's just 2.2 billion people around the world watching you right now.'”

It was a great way to open up. “Everybody started laughing,” Gaylord says. “It was like, 'Whatever, let's just go out there and have some fun,' and we did.” By the time Peter Vidmar stood on the horizontal bar as the final U.S. athlete in the final of six events, the U.S. had already broken a deadlock with China for the lead and secured the top spot on the medal podium. “It felt surreal, if that's the right word,” Connor says. “You always think, 'Oh, isn't this cool,' and then all of a sudden we're standing there and they play the national anthem and they put the medals around our necks. It's unbelievable.”

Day 2: Women's Team General

August 1, 1984

Sitting in a cramped dorm room at UCLA near the Olympic Village, the U.S. women's gymnastics team was glued to the television screen.

A few minutes' walk from Pauley Pavilion, gymnasts watched a live broadcast of the men's all-around competition and celebrated their victory by jumping and dancing around the venue. “It was so exhilarating,” said Michelle Dussert Farrell, a member of the 1984 U.S. women's gymnastics team.

But elation soon turned to anxiety as they realized the magnitude of the task ahead. “We knew there would be attention the next day,” she says. “We knew that inevitably, we would have the same expectations.”

But amid rising tensions on the eve of the women's team all-around competition, a sense of levity emerged from an unexpected source. When the women saw the now-iconic stars and stripes leotards for the first time, they initially laughed, thinking how ridiculous they would look in them. But once they tried them on, that feeling changed. [was] “It was the most comfortable leotard I'd ever worn,” Johnson-Clark said. “It was like a second skin.” With the snug new uniforms and the cheers of the home crowd, the U.S. won top scores in two of the four team events. But Romania proved too tough to beat, winning first place in the team all-around by one point, despite Julianne McNamara earning perfect 10s on floor exercise and uneven bars and Mary Lou Retton earning the top individual score. Still, the 1984 team became only the second U.S. women's team to medal in the team all-around and the first to win silver.

Day 3: Men's Individual All-Around

August 2, 1984

Vidmar called Pauley Pavilion home: The five-time NCAA champion from Los Angeles had competed there for several years before the summer of 1984 during his illustrious gymnastics career at UCLA.

Alongside fellow Bruins Gaylord and Tim Daggett, Vidmar's Olympic experience was the culmination of a long, arduous journey that began in Southern California. “It's a lifetime of hard work,” Vidmar said on the Resilience to Brilliance Podcast in January. “I was in the gym with both Gaylord and Daggett, and there were a lot of really tough days… It wasn't fun, and I think those are the times I learned the most about myself.” Coached from a young age by former U.S. Olympian Makoto Sakamoto (who later served as Vidmar's assistant coach at UCLA and on the 1984 Olympic team), Vidmar was always taught to test the limits of what he believed he could achieve in the gym.

“I tried to lead by example,” says Sakamoto, who was in his mid-30s when he coached Vidmar at UCLA. Training sessions at the time often involved him challenging his athletes to a friendly contest of handstand push-ups on the parallel bars. “At the end of practice, I'd say, 'Hey, see if you can beat me.' It was really tough,” Sakamoto recalls. “I never lost, but they were really trying.” Fueled by hard work and the fierce competitors he surrounded himself with at Westwood, Vidmar's triumphant final competition at his old college gym was a silver medal in the individual all-around, making him the first American man to medal in that event.

Day 4: Women's Individual All-Around

August 3, 1984

For the first time in days, Pauley Pavilion was silent, and the 9,023 spectators there were aware of the solemnity of the moment.

In the women's all-around, Romania's Ecaterina Szabo had a slight lead going into the final rotation, but after a back-and-forth battle, Mary Lou Retton needed a 9.95 on the vault to win the gold medal and a perfect 10 to win. In an instant, the cheers died down, the murmuring quieted. The weight of an entire nation was on the petite teenager's powerful shoulders. “I hope she's in good spirits on the vault today,” said ABC commentator Cathy Rigby McCoy, as Retton prepared for her run-up. For Retton, taking off into the air was easy. It was landing, Johnson-Clark said, that was her struggle. “You have to jump so high and explosively and somehow come to a complete stop and stay in stick position with your feet still. Mary Lou couldn't do that,” Johnson-Clark said with a laugh.

But when it mattered most, Retton left no doubt.

“Oh my gosh, she nailed the landing,” Johnson-Clark said. “I almost fell to my knees. The stars just lined up so perfectly. The last star just landed in the exact spot where I needed 10 points to win. There it was.” In a matter of seconds, Retton had gone from relative obscurity to Olympic superstardom. Her coach, Bela Karolyi, knew it right away. “Ten!” Karolyi yelled repeatedly as the arena erupted in applause. His excitement was so high it didn't even matter that he didn't have a place to stay that night. When Bob Condron, then director of media services and operations for the U.S. Olympic Committee, went to pick up Retton and Karolyi the next morning for a television appearance, they found the jovial coach wrapped in a quilt behind Pauley Pavilion. “He was sleeping in the alley,” Condron said. “We basically woke him up and got him.”

Night 5: Men's Individual Finals

August 4, 1984

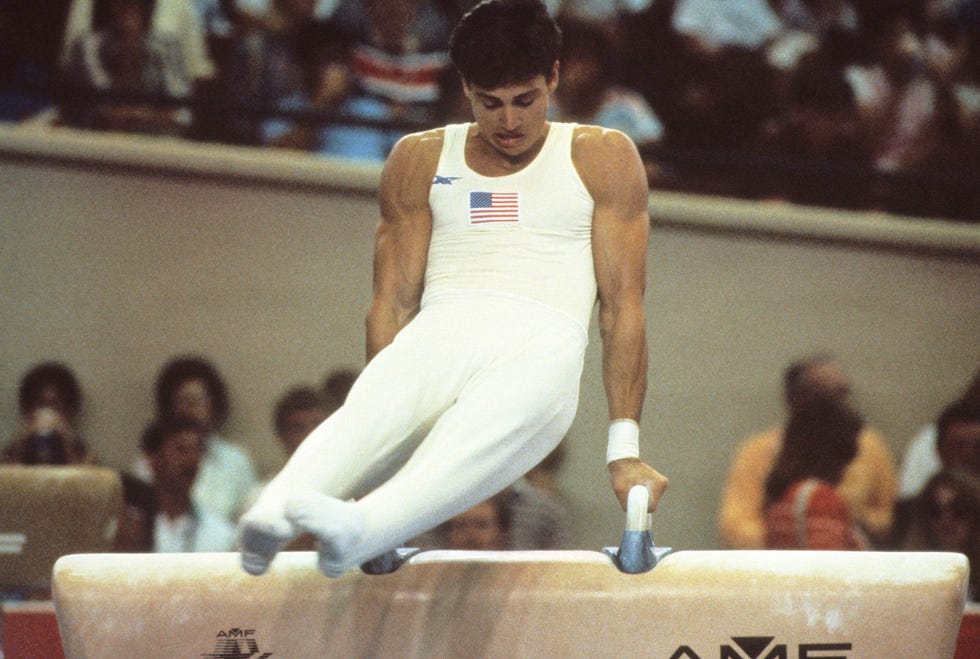

Four days after winning a historic gold medal in the team event, the U.S. men's team returned to Pauley Pavilion one last time.

With at least 18 medals up for grabs in six sports, the U.S. brought home six, capping an Olympic streak that defied expectations. “It was perfect timing for me,” Gaylord said. “I'm from Los Angeles, it was the LA Games, I went to UCLA and gymnastics was at Pauley Pavilion. Everything was lined up for success, and it was a great feeling. We came here to do something really special.”

Gaylord reached the podium three times on Saturday with a team-high silver and two bronze medals, solidifying her status as one of the most decorated gymnasts in U.S. gymnastics history. Vidmar's gold medal on the pommel horse and Conner's gold medal on the parallel bars added to the legend of the 1984 team. “There's a brotherhood there,” Conner said. “When we see each other, we hug each other in a different way because none of us could have been there without the rest of the guys on our team.” This bond, first forged in the fires of NCAA competition and then molded into a lasting friendship on the Olympic stage, played a key role in helping this group reach previously unforeseen heights in U.S. men's gymnastics. “They made a conscious decision,” Johnson-Clark said. “They left their egos at the door every time they walked into the gym to train together, compete together, and perform to the best of their ability together.”

Day 6: Women's Finals

August 5, 1984

On the sixth and final night of a week that transformed basketball Mecca Pauley Pavilion into a medal mine for USA Gymnastics, the women's team took to the mat for individual glory.

For the 24-year-old Johnson-Clark, it was the long-awaited end of an unconventional but legendary gymnastics career that began at age 12. “Not everything was perfect to go to the Olympics,” she said. “Nothing was really ideal, but it was perfect in a way. Perfect for me was because it allowed me to grow in spirit. It allowed me to grow in everything that's important to me, everything that makes me love this sport.” Johnson-Clark's bronze medal on balance beam ensured that at least one American woman would medal in all four events that night. McNamara's silver on floor exercise and gold on uneven bars set the pace, while Retton added three podium finishes to her already outstanding performances.

With 13 medals to their name, the “Silver Sisters” — as they still call themselves — left the '84 Games with a close friendship that will last into the future. At the center of it all was Johnson-Clark, captain and “team mom.” “I was able to follow (Kathy's) guidance in a lot of ways,” said Daselle Farrell, the youngest member of the '84 team. “I was able to rely on her experience, her support, her leadership, her ability to handle a lot of stress and pressure. We were all in the same shoes, so we relied on each other a lot.” After nearly quitting the sport altogether five years ago, Johnson-Clark fully embraced her role as a mother. She says the love and respect shared between the women today is just as strong as it was in 1984. “That's what makes it so deep and rich, that it started years before we shared that historic moment together,” Johnson-Clark said. “And we've supported and supported each other for the next 40 years.”