Scholars have proposed new regulatory models to strengthen workers' bargaining power.

As many as 300 million full-time jobs could be replaced by developing technologies, and workers are increasingly worried that a single software update or algorithm could make their job security obsolete.

In a recent paper, law professor Cynthia Estlund uncovers another hidden cost of the rise of technology: the decline of workers' bargaining power. Estlund explains that increasing automation has reduced the ability of American workers to negotiate better working conditions or higher wages. She argues that states should step in and use their regulatory powers to address this issue. Estlund proposes creating sector-specific regulations and involving workers in regulatory decision-making, a process she calls “sectoral co-regulation.”

Bargaining power is an employee's ability to negotiate and influence the terms and conditions of their employment. Estlund explains that this power has wide-ranging effects on workers' health, safety, and economic well-being. Without this leverage, workers are more likely to experience lower wages and benefits, less favorable employment terms, and increased workplace hazards and abuse.

In the United States, employees negotiate wages and working conditions through collective bargaining at their workplace. The federal government also sets national minimum standards for basic working conditions to protect workers who cannot bargain collectively.

Workers have considerable bargaining power when other jobs are readily available and leaving them would incur significant costs to their employers.

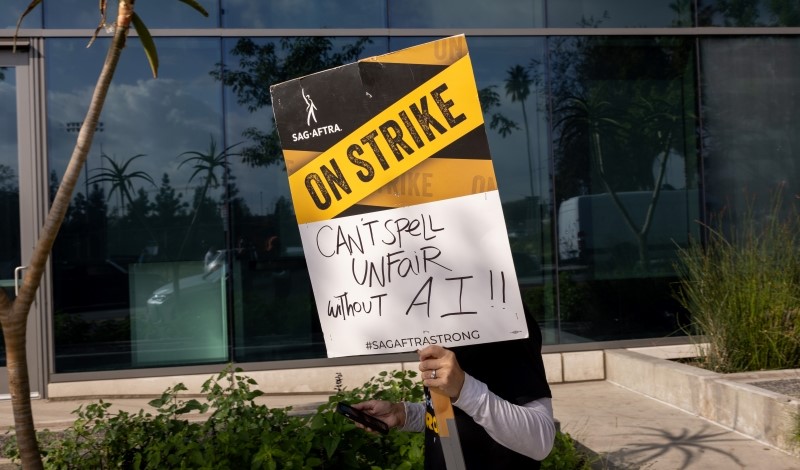

But Estlund argues that technological advances are reducing workers' influence because employers can use technology to replace them.

Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and robotics can replicate a wide range of human capabilities that were once thought of as “uniquely human.” They can complete complex tasks faster and more accurately than humans, improving business performance and reducing costs.

For example, technology allows companies to outsource certain tasks or phase out full-time positions. Estlund explains that technology has made it cheaper to find suppliers and take advantage of cheaper labor costs. Surveillance and communication technologies have made these relationships more feasible.

Companies are also adopting “just-in-time” scheduling software, a tool to manage labor costs by scheduling employees based on fluctuating consumer demand. This new technology allows companies to replace full-time employees with part-time or temporary workers.

According to Estlund, these technological developments and their impact on workers' bargaining power call for a restructuring of how labor standards are negotiated and set in the United States.

Estlund argues that the system needs to rely more on state regulatory power to raise labor standards. He proposes a new regulatory model called “sectoral co-regulation,” in which states, with worker input, would create regulations based on specific industries.

To include workers in the regulatory process, Estlund suggests that states should use the power of collective bargaining and union representation. In this “co-regulation” approach, workers have an institutionalized role in setting and enforcing labor standards.

Estlund explains that including workers in the regulatory system is essential because they have direct knowledge and interest in the enforcement and improvement of workplace rights and labor standards. By making workers part of the process, Estlund argues, regulators can develop labor standards that are more responsive to workers' specific needs.

Estlund points out that a co-regulatory approach would not establish uniform labor standards, but rather would set industry-specific standards that cover all workers in a particular economic sector. Estlund argues that the bargaining model produces higher-level, more specialized standards that are not feasible for all industries.

Some states have already enacted industry-specific regulations with worker input. For example, California recently enacted law, AB 1228, which sets a $20 minimum wage for fast food workers and creates the Fast Food Council, a regulatory body that can recommend new standards specific to the fast food industry. The council is made up of nine voting members, including two representatives of fast food workers and two representatives of employee advocacy groups.

California Governor Gavin Newsom said the legislation would “give hardworking fast food workers a voice and a seat at the table.”

As technology advances and companies find new ways to incorporate it into their work, Estlund argues that workers' bargaining power will continue to decline within the existing framework, but by including workers in the regulatory process and setting standards for specific industries, regulators can help workers achieve better wages and working conditions, he concludes.