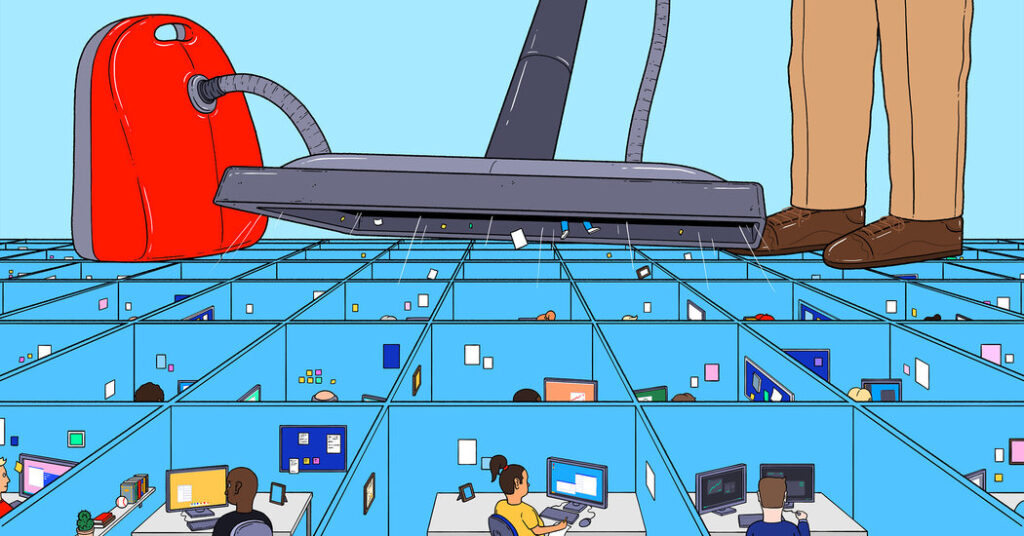

Silicon Valley prides itself on disruption: startups develop new technologies, upend existing markets, and overtake incumbents. This cycle of creative destruction gave us the personal computer, the Internet, and the smartphone. But in recent years, a few incumbent technology companies have maintained their dominance. Why? We think they learned how to absorb potentially disruptive startups before they could pose a competitive threat.

Let’s look at what’s happening with the leading generative artificial intelligence companies.

DeepMind, one of the early prominent AI startups, was acquired by Google. OpenAI, a nonprofit founded to challenge Google's dominance, raised $13 billion from Microsoft. Anthropic, a startup founded by OpenAI engineers wary of Microsoft's influence, raised $4 billion from Amazon and $2 billion from Google.

Last week, news broke that the Federal Trade Commission was investigating Microsoft's deal with Inflection AI, a startup founded by DeepMind engineers who formerly worked at Google. The government seems interested in whether Microsoft's agreement to pay Inflection $650 million in a licensing deal, while simultaneously firing most of its engineering team and dismantling the startup, was an antitrust loophole.

Microsoft has defended its partnership with Inflexion. But are governments right to be worried about such deals? We think so. In the short term, partnerships between AI startups and big tech companies bring the startups loads of cash and the hard-to-get chips they want. But in the long term, it's competition, not consolidation, that drives technological progress.

Today's technology giants were once small start-ups that built their businesses by figuring out how to commercialize new technologies: Apple's personal computers, Microsoft's operating systems, Amazon's online marketplace, Google's search engine, and Facebook's social network. These new technologies did not compete with existing technologies, but rather offered new ways to circumvent them and subvert market expectations.

But the pattern of new companies innovating, growing, and overtaking incumbents seems to be over. The tech giants are old: Apple and Microsoft were founded in the 1970s, Amazon and Google in the 1990s, and Facebook in 2004 – all of them more than 20 years old. Why haven't new competitors emerged to disrupt the market?

The answer is not just that today's big tech companies are better at innovating: The best available evidence — patent data — suggests that innovation is more likely to come from startups than from incumbents, and economic theory predicts that too.

Incumbents with large market shares have little incentive to innovate because new revenue generated by innovation may cannibalize revenue from existing products. Talented engineers are more enthusiastic about stock in startups with the potential for exponential growth than stock in large companies that don't tie them to the value of the projects they work on. And incumbent managers are rewarded for developing incremental improvements that satisfy existing customers rather than disruptive innovations that may devalue the skills and relationships that empower them.

Big tech companies have learned to stop the cycle of disruption. By investing in startups developing disruptive technologies, they gain information on competitive threats and the power to influence the startups' direction. Microsoft's partnership with OpenAI highlights the issue. In November, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said customers had nothing to worry about if OpenAI suddenly disappeared because “we have the talent, the compute, the data, everything.”

Of course, incumbents have always benefited from squeezing out competitors. Earlier technology companies like Intel and Cisco understood the value of acquiring start-ups with complementary products. Today, technology executives are more likely to buy into outside start-ups than into new products. Their core markets can pose dangerous competitive threats, and today's tech giants, because of their sheer size, have the money to exploit them: When Microsoft went to trial for antitrust violations in the late 1990s, it was valued at tens of billions of dollars; today it's worth more than $3 trillion.

In addition to funding, tech giants can use their access to data and networks to reward startups that collaborate and punish those that compete. Indeed, this is one of the claims made by the government in its new antitrust lawsuit against Apple (Apple denies the claims and is seeking to have the case dismissed). They can also use their political connections to push for regulations that act as competitive bulwarks.

Remember Facebook's ads calling for increased internet regulation? Facebook didn't buy ads for charity. Facebook's proposal “consists primarily of implementing requirements for content moderation systems that Facebook has already implemented,” tech research site The Markup concludes. This gives the company a first-mover advantage over its competitors.

If these tactics fail to keep an upstart from competing, the tech giants can simply buy it. Mark Zuckerberg made this clear in an email to colleagues before Facebook bought Instagram. He wrote that a startup like Instagram “could be very disruptive to us if it grew to scale.”

Tech giants also have repeat business relationships with venture capitalists. Startups are risky investments, so for a venture fund to be successful, at least one of its portfolio companies must be exponentially profitable. As initial public offerings decline, venture capitalists are increasingly turning to acquisitions to make profits. Venture capitalists know that only a few companies can buy startups at those prices, so they maintain friendly relationships with tech giants to try to steer startups into deals with incumbents. That's why some prominent venture capitalists are against tougher antitrust laws: it's bad for business.

Joint acquisitions may seem harmless in the short term — some alliances between incumbents and startups can be productive — and acquisitions give venture capitalists the benefits they need to convince investors to put more capital into the next wave of startups.

But collusion hampers technological progress. When a big tech company acquires a startup, it may shut down the technology. Or it may repurpose the startup's talent and assets for its own innovation needs. And even if it does neither, the structural barriers that stifle innovation at big incumbents can sap the creativity of the acquired startup's employees. AI seems like the quintessential disruptive technology. But as more and more disruptive startups that pioneered it are linked to big tech companies, AI may become little more than a way to automate search engines.

The Biden administration can take steps to address this issue.

Earlier this year, the FTC announced it was investigating big tech companies' deals with AI companies, which is a promising start, but the rules that enable collusion need to change.

First, Congress should expand “interlocking officer” laws (which prohibit company directors and officers from serving on the boards of competitors) to prevent tech giants from appointing employees to the boards of startups. Second, courts should punish dominant companies that discriminate in access to their data or networks because a company is a potential competitor. Finally, as Congress moves to regulate AI, it should be careful to craft rules that do not entrench incumbents.

Finally, the government should identify a list of potentially disruptive technologies, starting with AI and virtual reality, and express a principled opposition to mergers between big tech companies developing those technologies and startups. This policy might make life harder for venture capitalists who like to give speeches about disruptive change and then go for drinks with their friends from Microsoft's corporate development department. But it would be good news for founders who don't want to sell their startups to monopolies, but want to sell products to customers. And it would be good for consumers, who have long lived without competition, despite being dependent on it.

Mark Lemley is a professor at Stanford Law School and co-founder of legal analytics startup Lex Machina, and Matt Wansley is an associate professor at Cardozo School of Law and was general counsel at self-driving startup nuTonomy.

The Times is committed to publishing Diverse characters To the Editor: Tell us what you think about this article or any other article. Tips. And here is our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section Facebook, Instagram, Tick tock, WhatsApp, X and thread.