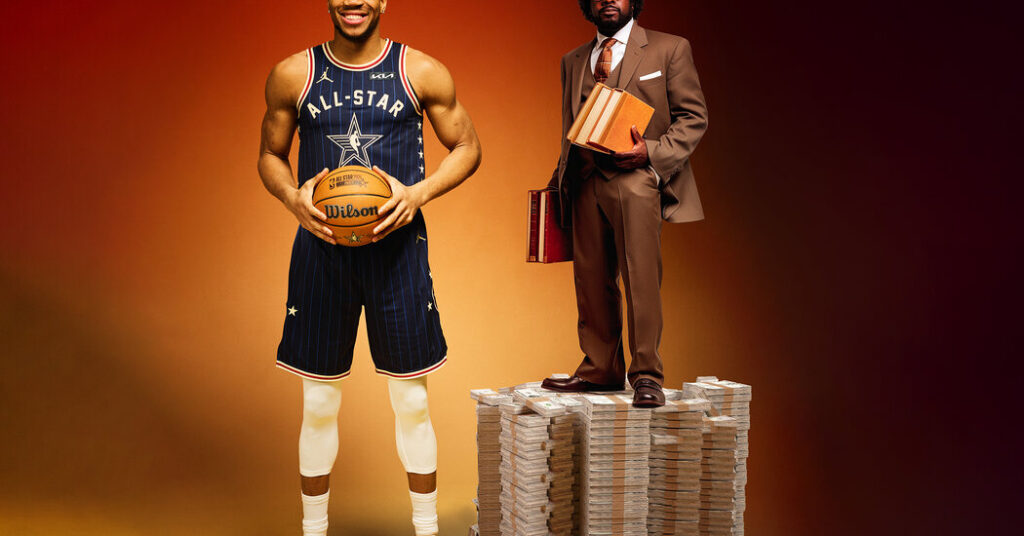

Demand for Wall Street's top lawyers is now so high that bidding wars between law firms for their services resemble the frenzy between teams trying to sign a star player.

Eight-figure compensation packages, rare a decade ago, are becoming increasingly common among top corporate lawyers. their game, and many of these new big names have one thing in common: private equity.

In recent years, lucrative private equity giants such as Apollo, Blackstone and KKR have amassed trillions of dollars in assets by expanding beyond corporate acquisitions into real estate, private lending and insurance. As demand for legal services from these firms has soared, they have become major revenue generators for law firms.

This has driven up legal fees across the industry, including at some of Wall Street's most prestigious firms, such as Kirkland & Ellis, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, Davis Polk, Latham & Watkins, and Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Lawyers with close ties to private equity are increasingly enjoying the same pay and prestige as the star lawyers who represent America's top companies and advise them on high-profile mergers, acquisition battles, and litigation.

Many compared it to a star-driven system like the NBA's, while others worried that salaries would get increasingly unaffordable, putting a strain on law firms, who would be forced to tighten their budgets to keep top talent at bay.

“$20 million is the new $10 million,” said Sabina Lippman, partner and co-founder of legal recruiting firm Lippman Jungers. Over the past few years, at least 10 law firms have either spent roughly $20 million or more a year to bring in their most high-profile lawyers, or acknowledged to Lippman that they needed to do so.

A recruiting partner at one law firm said a $20 million compensation package is typically only awarded to someone who can bring in more than $100 million in annual revenue for the firm.

Last year, Kirkland's six partners, including those hired during the year, earned at least $25 million each, according to people who were not authorized to discuss pay publicly. Several others in the London office made about $20 million.

A partner at one law firm said top lawyers' salaries have roughly tripled in the past five years.

The take-home pay of top lawyers is closing in on that of the heads of major banks: Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the U.S., made about $36 million last year, while David Solomon of Goldman Sachs made about $31 million in the same period.

At the center of this movement is the 115-year-old Chicago law firm Kirkland, which was an early player in wooing private-equity clients at a time when few rivals saw them as big-money makers. About a decade ago, Kirkland began poaching top law firms from rivals, many of them based in New York, who had longstanding ties to the biggest private-equity firms.

This has led to fierce competition among big law firms such as Simpson, Latham, Davis Polk and Paul, Weiss, as some have changed compensation structures or expanded budgets to entice their stars to quit, while others have responded by attacking Kirkland and setting up their own private equity businesses.

“I don't think companies should just be on the defensive when it comes to talent,” said Scott Yaccarino, co-founder of legal recruiting firm Empire Search Partners. “They have to be on the offensive as well.”

Lawyers have been making millions for more than a decade. When Scott A. Barshay, a top M&A lawyer, left Cravath, Swaine & Moore to join Paul, Weiss in 2016, his $9.5 million compensation shocked the industry. (Mr. Barshay's compensation has increased substantially since then, according to two people familiar with the deal.)

But the recent surge in salaries has been dizzying, and the pool of available lawyers has expanded dramatically. Combined with aggressive poaching, the landscape of how big firms operate is rapidly changing. Kirkland is guaranteeing some of its hires fixed equity in the partnership for several years, according to people familiar with the deals. In some cases, it's extending forgivable loans as sweeteners.

Kirkland last year poached Alvaro Membrillera, a prominent London private-equity lawyer whose main client is KKR, from the law firm Paul, Weiss for about $14 million and multiyear guarantees, according to two people familiar with the deal.

White & Case recently hired O. Keith Hallam III, a partner at Cravath who works on private-equity clients, for about $14 million a year, according to a person familiar with the deal. The firm also hired Towry M. Zeitzer, a private-equity lawyer at Paul, Weiss & Co., for roughly the same amount, according to another person familiar with the deal.

For some, this changing environment means a more meritocratic system in which partners can expect to be compensated based on talent rather than seniority. Cravath, the well-known 205-year-old law firm, had a so-called lockstep system linked to seniority for many years but revised it in 2021. Debevoise & Plimpton is one of the few firms that continues to follow the lockstep model.

“Law firms have become much more commercial in the way they are run,” said Neil Barr, chairman and managing partner at Davis Polk. “Law firms are being run more like corporations than traditional partnerships, which has led to more rational business behavior.”

Kirkland's early bet on private equity has paid off big time: Private equity firms around the world will have $8.7 trillion in assets under management in 2023, according to data provider Preqin, more than five times the amount at the start of the 2007 financial crisis. Blackstone alone manages more than $1 trillion in assets, while other firms including Apollo, Ares, KKR and Brookfield collectively manage trillions of dollars more.

As its private equity business took off, Kirkland's clients began bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars in business each year, and by 2023 Kirkland had gross revenues of more than $7 billion, making it the world's highest-revenue law firm, according to American Lawyer magazine's annual rankings.

Even single law firms like Blackstone and KKR can draw legal work from their collections of corporations, banks and other businesses. Blackstone's main law firm is Simpson, for example, but the company paid $41.6 million in 2023 for Kirkland, one of its secondary firms, according to regulatory filings.

“The private equity clients of these companies are making money,” said Mark Rosen, CEO and chairman of legal recruiting firm Mark Bruce International.

Simpson, a prominent Wall Street firm with roots in the Gilded Age and one of the largest private-equity businesses, has been a target for poaching by Kirkland. A person with knowledge of the rivalry described Simpson as Kirkland's “farm team.” “As a firm, we have the utmost respect for Simpson Thacher,” Kirkland spokeswoman Kate Slustedt said in an email.

At least seven of Simpson's top partners, including Andrew Calder and Peter Martelli, have moved to Kirkland in the past decade. Kirkland also poached Jennifer S. Perkins, a star Latham lawyer who represented KKR on several deals, to its private-equity division.

Mr. Calder and Kirkland Chairman John A. Burris were among the partners who made at least $25 million last year, according to three people with knowledge of the compensation.Mr. Calder and fellow Kirkland partner Melissa D. Kalka work closely with Global Infrastructure Partners, the private-equity firm that recently announced a deal to sell to BlackRock for $12.5 billion.

In 2023, Paul Weiss, which counts Apollo Global Management as a key client and is actively building its private equity business, poached several Kirkland lawyers to expand its London office. The firm also poached Eric J. Wedel, whose clients include Bain Capital, KKR and Warburg Pincus, from Kirkland, and Jim Langston, another lawyer who specializes in private equity, from Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton.

Simpson has changed its pay structure over the past year to better compete with Kirkland's and other rivals. “We made the intentional decision to adjust our pay structure to attract and retain the best talent for strategically important roles across our global platform,” Alden Millard, chairman of Simpson's executive committee, said in an email.

One sign of the frenetic nature of the recruiting drive is the use of multi-year pay guarantees to attract lawyers. That tactic fell out of favor after Dewey & LeBoeuf filed for bankruptcy in 2012 and was unable to pay millions of dollars in fixed compensation and bonuses it had promised to partners. Now, a different kind of guaranteed payout is gaining popularity.

Some companies offer new employees partnership shares for a fixed period of time (usually between two and five years). Such offers are attractive because they guarantee a percentage of the company's profits, regardless of the company's performance throughout the year.

The frenzy has also boosted salaries for lawyers without private equity ties. Freshfields, a major British law firm that is building a U.S. presence, is hiring lawyers in the $10 million to $15 million range and offering some additional salary guarantees, according to three people with direct knowledge of compensation details.

“Law firms want people who are culture-driven,” says recruiter Lippman, “but at some point there's a big difference between the firms and everyone becomes priced out.”