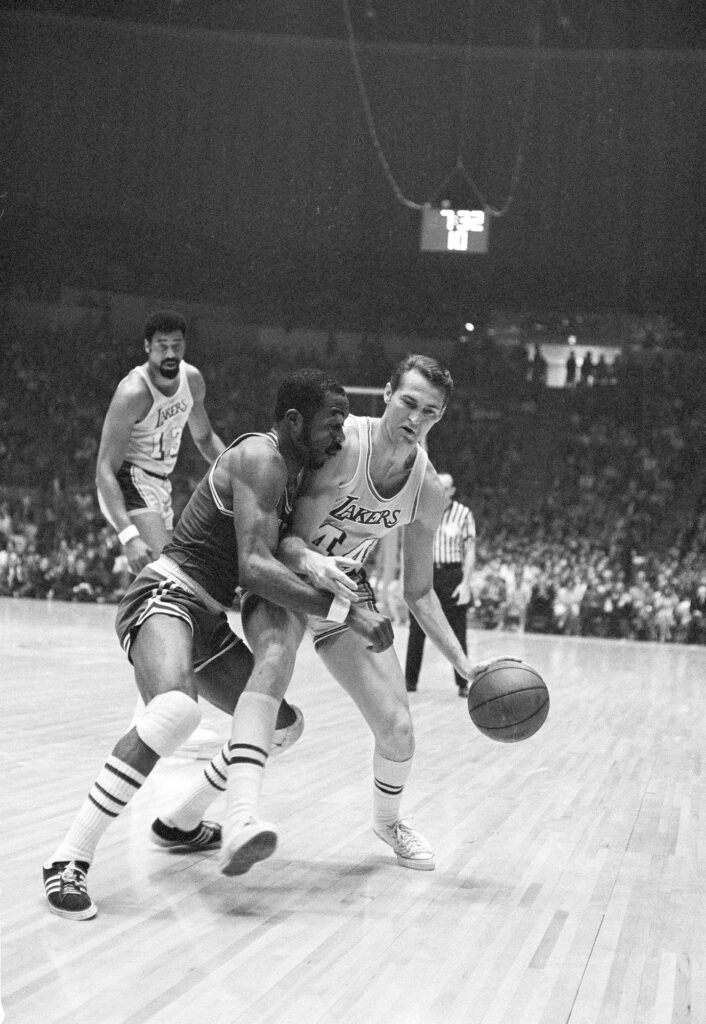

West became one of the most accomplished players in the history of the National Basketball Association (NBA). He was widely regarded as one of the league's greatest players and earned the nickname “Mr. Clutch” for his late-game performances with the Lakers.

His most famous shot came in Game 3 of the 1970 NBA Finals against the New York Knicks: With three seconds left and the Lakers down by two, West took an inbounds pass, dribbled three times and then fired a 60-foot rainbow shot from well behind the half-court line that fell into the basket (sending the game into overtime, where the Lakers lost).

“The crowd was going crazy, everybody was going crazy, and we were looking up at the scoreboard wondering what just happened, what on earth just happened,” Knicks guard Walt Frazier, who guarded West for much of the game, later told the Los Angeles Times.

After hanging up his No. 44 jersey in 1974, West enjoyed an even more illustrious second life as the league's top executive. His visionary draft picks, timely trades and talent-driven talent led the Lakers to dominance in the NBA in the 1980s and early 2000s, reaching eight Finals and winning four championships.

But for all the accolades, West has also been his own harshest critic and one of the most tortured figures in sports.

West, who played in the 1960s and early 1970s, led the Lakers to nine NBA Finals appearances but lost eight times. Six of those losses came at the hands of Bill Russell's Boston Celtics, and West developed an aversion to the color green and never wanted to visit Boston again.

“That loss left a scar on me that remains with me to this day,” he wrote in his 2011 memoir, “West by West,” co-written with Jonathan Coleman. All of his miracle shots against the Knicks were for naught, and the Lakers lost the championship in seven games.

His subsequent performance as general manager and executive vice president of the Lakers seemed to bring more pain than joy, at one point leaving him hospitalized for a nervous breakdown.

He once called his perfectionism “a terrible burden because I can never really be happy with anything.”

In his memoir, West revealed that he grew up in rural West Virginia with a reclusive mother and a father who beat him, and that he struggled with depression his whole life. After one particularly violent assault, West threatened to kill his father with a shotgun he kept under his bed.

This harsh upbringing, he wrote, “most likely molded me into a strong-willed and pathologically competitive person, a tormented and rebellious person with a hole in my heart that ultimately could never be filled.”

Hunting, fishing and basketball were his escapes from his home life. He began shooting at a young age at wire baskets mounted on the sides of bridges. Accuracy was key, as the ball would roll down the riverbank if it wasn't in. He practiced constantly, in the rain, mud and snow, sometimes shooting balls until his fingers were bloody. In doing so, he developed the technically perfect jump shot that would become his trademark.

Even though the NBA hadn't yet adopted the three-point shot, the 6-foot-3 West averaged 27 points per game, the fourth-highest total in league history, and was named to the All-Star team in 14 seasons with the Lakers. He was also a defensive stopper, rushing for rebounds, rushing for steals and taking charges so hard he broke his nose nine times.

“Watching him now, more than 40 years later, is like watching a human basketball camp,” sports journalist Bill Simmons wrote in The Book of Basketball. “His jump shot is perfect. His defensive technique is perfect. His dribbling is like an infomercial.”

West was at his best when the stakes were the highest: His playoff average of 29.1 points per game was surpassed only by Michael Jordan and Allen Iverson, who played decades after West and were masters of the 3-point shot. The late Lakers play-by-play announcer Chick Hearn, nicknamed “Mr. Clutch,” said West always wanted the ball when the game was on the line.

“He knew he could make any shot in the last five seconds,” Hahn told the Press-Enterprise. “There were so many times I saw him get up, take a 20-foot jump shot and keep running to the locker room because he knew the shot was going to go in.”

In his second season with the Lakers, he singlehandedly saved his team's Game 3 victory over the Celtics in the 1962 NBA Finals when, having made two baskets to tie the game, he stole an inbounds pass and drilled a buzzer-beating layup to seal the win.

“Jerry West will rip your heart out,” Celtics coach Red Auerbach said in 1965. Referring to Mr. West's boyish, clean-cut appearance, he added, “Who could expect that from such an innocent guy?”

And yet West's talented teams always seemed to fall just short. In 1969, he became the first, and still only, member of a losing team to win the Finals Most Valuable Player award.

Despite averaging nearly 38 points per game, the Lakers were overwhelming favorites to win the championship and featured future Hall of Famers Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor, but they were defeated by the Celtics in seven games.

The loss devastated West so much that he considered quitting the sport and dynamite-ing the green Dodge Charger he received as MVP. Even several Celtics players felt they'd been cosmically wronged. After the final buzzer, Celtics forward John Havlicek told West, “Jerry, we love you. We hope you win. You deserve it more than anybody that's ever played this game.”

“Through the clouds,” as he put it, the Lakers finally broke through in 1972. By then, Baylor was retired and Chamberlain and West were past their prime. Still, the team won 69 of 82 regular season games and recorded 33 straight wins, which remains a league record. In the NBA Finals, the Lakers swept the Knicks in five games, and West finally got his championship ring.

But West paid little attention to his growing collection of memorabilia.

“My dad had hundreds of trophies, but he threw away most of them,” one of West's sons, Mark, told reporters, according to the Press-Enterprise. “He gave us a basketball when he scored his 20,000th point, and he let us take it outside and play with it when we were kids.”

Experts collect often-overlooked gems

West retired from playing in 1974 at age 36 but returned to coach the Lakers in 1976. Though his teams made the playoffs all three years, he often chastised his players for not working hard enough and lamented their losses. In “West by West,” former Lakers player and coach Pat Riley recalls that West contemplated suicide.

“When he was coaching in Kansas City, we were on the balcony of a hotel on the 15th floor and he was looking over at me and I just said, 'Screw it,'” Riley said.

The front office was a better fit for West, who spent three years as a scout for the Lakers before being named the team's general manager in 1982. Led by point guard Earvin “Magic” Johnson and center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the team established a fun, sprinting style known as Showtime, winning two more NBA titles by the time West took the helm. His shrewd trades got Showtime off the ground.

The team's success meant the Lakers typically picked low in each year's NBA draft, by which point most of the best prospects had departed, but West still unearthed overlooked talents like James Worthy and A.C. Green and traded for key players like Michael Thompson and Byron Scott, who helped the Lakers win three more NBA titles in the 1980s.

“West saw things that other people didn't see, and that was his genius,” said Sports Illustrated basketball writer Jeff Pearlman, who has written two books about the Lakers.

In the summer of 1996, West called his front office's biggest achievement a trade that traded high school sensation Kobe Bryant, who had been drafted by the Charlotte Hornets, for Shaquille O'Neal, then the league's leading center. The trade set the Lakers up for another championship run under head coach Phil Jackson, who had led the Chicago Bulls to six NBA championships and whom West had hired in 1999.

But as the Lakers played better and fan expectations grew, West seemed to struggle.

Too nervous to watch the big game, he passed the time by wandering the arena's aisles or listening to music on his car radio while driving down the Ventura Freeway. Instead of soaking up the applause at one of the Lakers' many championship parades, he sat out the event and focused on building his team for next season.

In 2000, West developed an irregular heartbeat and resigned from the Lakers just weeks after they won their first NBA title in 12 years.

But he wasn't done yet.

Two years later, West shocked the basketball world when he was named president of basketball operations for the Memphis Grizzlies. After his huge success with the Lakers, West said he relished the challenge of turning around a struggling NBA team. After the Grizzlies reached the playoffs in 2004, West was named NBA Executive of the Year for the second time. He spent his final years in the league as a board member for the Golden State Warriors and Los Angeles Clippers.

“I didn't think I was good enough”

Jerome Allan West was born on May 28, 1938, in Chelian, West Virginia, the fifth of six children. His father was a mining electrician and union activist who moved from job to job, leaving the family on the brink of poverty. West once said he ate soup for dinner six days in a row, and vitamin deficiencies initially made him small for his age.

When his older brother, David, his parents' favorite son, was killed in the Korean War, West was deeply affected, he said, and one of the consequences of that death was his determination to succeed on the basketball court.

“I wasn't jealous of him, but I had a lot to live up to,” he wrote in his memoirs.

In 1956, he led his East Bank High School team to a state championship, then earned a basketball scholarship to West Virginia University, where he became a statewide hero when he led the Mountaineers to the NCAA finals in 1959. Foreshadowing his professional failure, West Virginia lost by one point to the University of California, Berkeley.

In 1960, he was co-captain, along with Oscar Robertson, of the U.S. Olympic basketball team that beat the Soviet Union to win the gold medal. He was drafted by the Lakers soon after, but his deep self-doubt continued. “I never thought I was good enough to play in the NBA,” he later told Sports Illustrated. “I really didn't.”

West's first marriage, to his college sweetheart, Martha Jane Kane, ended in divorce. In 1978, he married Karen Bua. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Before fully retiring, West had been involved in 22 NBA Finals as a player, consultant or team executive — more than league icons Auerbach and Jackson. He was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1980, named one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history in 1996 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, from President Donald Trump in 2019.

But he didn't say much about his win.

“The pain of losing is so much stronger than the joy of winning,” he told Sports Illustrated.