Felicia Rangel-Samponaro never learned the little girl’s name, but she remembers everything else about her.

Each time Rangel-Samponaro crossed the U.S. border to work with migrant children on the Mexican side, the 10-year-old would greet her with a hug and a smile, enthusiasm Rangel-Samponaro rewarded with books.

But that didn’t last.

“It wasn’t even a month before I watched her go from smiling and ‘Hi Felicia!’ to she stopped bathing, she stopped washing her hair,” Rangel-Samponaro said.

Eventually she stopped coming all together.

You see what happens to a child, Rangel-Samponaro said, and you never forget.

Kayleen, one of the local iACT coaches, during a water break at a immigrant shelter.

(Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

She tells the story while sitting in the shady courtyard of a two-story storefront about a block from the Mexican side of a border the U.S. government has lined with razor wire. A few minutes earlier, a half-dozen children filled the patio, sitting on metal chairs at a folding table, going over school lessons with two teachers.

While politicians have implemented draconian ways to stem the flow of asylum seekers inundating the U.S.-Mexico border, Rangel-Samponaro is among those caring for the most innocent and desperate migrants — the children. More than four years ago she started the Sidewalk School, which has provided free education, medical care and food to more 800 children whose lives have been put on hold as their parents wait out the lengthy asylum process.

“When a child is seeking asylum, education stops for that child. You’re sitting in these encampments for months, years,” Rangel-Samponaro said. “A child needs to learn. But also focus on something else because they don’t understand what’s happening.

“Children are depressed, they’re angry, they have all of these feelings. But they don’t know how to let those feelings out in a constructive way.”

It’s a problem one school alone can’t solve. Which is where soccer comes in.

“I don’t think you can undervalue the power of play for children,” said Sara-Christine Dallain, the executive director of iACT, a Los Angeles-based humanitarian nonprofit that has used soccer to teach teamwork, respect, responsibility and pride to children in refugee camps around the world. Now with help from organizations including the Sidewalk School and financial backing from Angel City FC, iACT expanding its work into northern Mexico.

“They’re learning language, they’re learning teamwork. They’re learning a really incredible social skill,” Dallain said. “For children who have experienced a lot of hardship and trauma and uncertainty, the opportunity to just move their bodies and be children in a structured environment will go a really long way.”

Sara-Christine Dallain, executive director of iACT, tests her soccer skills against a pair of children at the Senda de Vida migrant shelter in Reynosa.

(“Fish” for Angel City)

Dallain has experienced the power of play firsthand. During the last 15 years, iACT has worked with more than 43,000 children who have been displaced by war and conflict scattered throughout six countries, mostly in Africa. Soccer, she found, is a universal language understood by children from Armenia to Zaire.

“We focus on soccer because sports programming for children is regularly under-prioritized in the global humanitarian response, and, in fact, is often seen as unimportant,” she said. “Yet when we sit and listen to families, what we hear is that they actually find it extremely important. Parents want opportunities for their children to play.

“It was listening to parents that led us to soccer.”

The need for a program focused on children at the U.S.-Mexican border has never been greater. The Border Patrol registered nearly 190,000 “encounters” with migrants at the U.S.-Mexican border in February, and in recent years the number of encounters involving children has increased. Another 3 million-plus migrants have pending asylum claims, triple the number in 2019, while tens of thousands more have gathered at the border, hopeful of getting an appointment to make asylum petitions.

That led iACT to the Senda de Vida migrant shelter in Reynosa, which sits at the end of an unpaved gravel road just across the border from McAllen, Texas. After working with some of the world’s most world’s most desperate refugees in places like Darfur and the Central African Republic, Dallain found the situation along the border even more heartbreaking.

“It felt very different,” she said. “It hit me more emotionally and it was harder to see the circumstances that families are in here. I think, ‘OK, if I was a parent, I’ve gone through this journey, what would I want for my child?’

“Beyond the basics, I would want my child to experience like joy and to forget about circumstances that we’re in. You want them to get that childhood back.”

On a recent chilly morning, Abraham Reyes helps the children in the Reynosa shelter recover bits and pieces of their childhoods. One of four local coaches hired by iACT to work in Senda de Vida, Reyes, wearing shorts and a yellow T-shirt underneath a blue Notre Dame football hoodie, drags a large bag of soccer balls and other equipment into a long, narrow space boxed in by high cinderblock walls.

Soccer coach Abraham Reyes instructs children at an immigrant shelter in Reynosa, Mexico.

(Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

Plans to make the space into a school have been paused, so in the meantime it has become a cement playing field for about three-dozen children, many who play barefoot or in flimsy plastic flip-flops.

“By playing we are trying to get the children distracted from everything that is happening,” Reyes, once an elite-level soccer player, said in Spanish. “Support them. Let them forget a little the issues that have happened during their journey.”

By the time Reyes and the other coaches enter the shelter just before 9 each morning, the children, most between the ages of 5 and 13, already are lined up at the door to the play space, many wearing hand-me-down cotton sweatshirts and wool caps against the morning chill.

They come from Venezuela, Mexico, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras and Ecuador, brought by relatives fleeing crushing poverty, gang violence or political turmoil at home. Most endured harrowing ordeals only to see their trips stall a few hundred yards short of a border teeming with thousands of others who have made the same precarious journey.

For many children, things have gotten worse, not better, since arriving. Craving attention they swarm newcomers to their play space, but mostly remain silent, content to simply be seen and acknowledged.

“It is a very difficult situation,” continued Reyes, whose is studying Creole so he can communicate more personally with the growing number of Haitian migrants reaching the border. “There are children who have seen someone killed or abused. They have a lot of traumas. Because of what they’ve been through, everyone is living with fear.”

Senda de Vida (Path of Life) was built by pastor Hector Silva atop the garbage dump where he once lived. A large, perpetually optimistic man with boundless patience and close-cropped hair that has gone gray at the temples, Silva said God told him to built a refuge there “to help the widow, the orphan who come from other nations.”

Instead he built two.

Pastor Hector Silva says God told him to build a shelter in Reynosa, Mexico, “to help the widow, the orphan, who come from other nations.”

(Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

Senda 1, where the iACT program is based, can hold as many as 1,300 people behind high whitewashed walls and heavy gates manned by security guards. There are rules against smoking, drinking and carrying weapons and inside families share simple, unfurnished, blue-and-white structures, each measuring about 36 by 45 feet with a thin plastic mat for a floor.

What was missing was structured activities for the nearly 150 children staying there, often indefinitely, as they wait out the vagaries of a broken asylum process.

“We saw the opportunity. There was space. There were a lot of children,” said Dallain, who brought her soccer program to the shelter 13 months ago. “We know play has an impact on child development. If children have a safe space to play, we know they’re going to have fun, they’re going to feel safe, they’re going to develop.

“They’ve gone through so much to get to this point. You can’t put a value on what it means for them to have these spaces.”

The coaches begin the roughly 2½-hour sessions by gathering the children in a circle. A soccer ball is rolled to each child, a prompt for them to say their name, age, what country they’re from and then to share something about themselves, such as their favorite color or animal. Despite wandering attention spans and the wide range in age of the players, Reyes and his assistant coaches manage to keep the sessions organized and well-run.

For some kids, however, the soccer program — which many refer to as “the academy” — is nothing more than a break in an otherwise endless series of gray days stuck inside the small shelter.

“It’s so boring here,” complained a 13-year-old Mexican girl, who fought the boredom by showing up every morning to play soccer.

As in the African refugee camps, where the iACT program was introduced, then perfected, there is a point to everything and the point of the first morning exercise is to make sure every child feels welcome and to create positive relationships and a sense of community. Making sure the children are safe, empowered, can make choices and feel they are being seen, heard and supported physically and emotionally are all core tenets of the instruction.

The kids then break into groups and run relay races around small orange cones, learning teamwork and cooperation. The mornings often end with competitive games between co-ed teams in which even the smallest kids display surprising skill. (The best player is arguably a tall, thin girl wearing a long ponytail, blue jeans and a rainbow-colored shirt with the word “Dreamer” stitched across the front, who is virtually unbeatable in goal.)

1

2

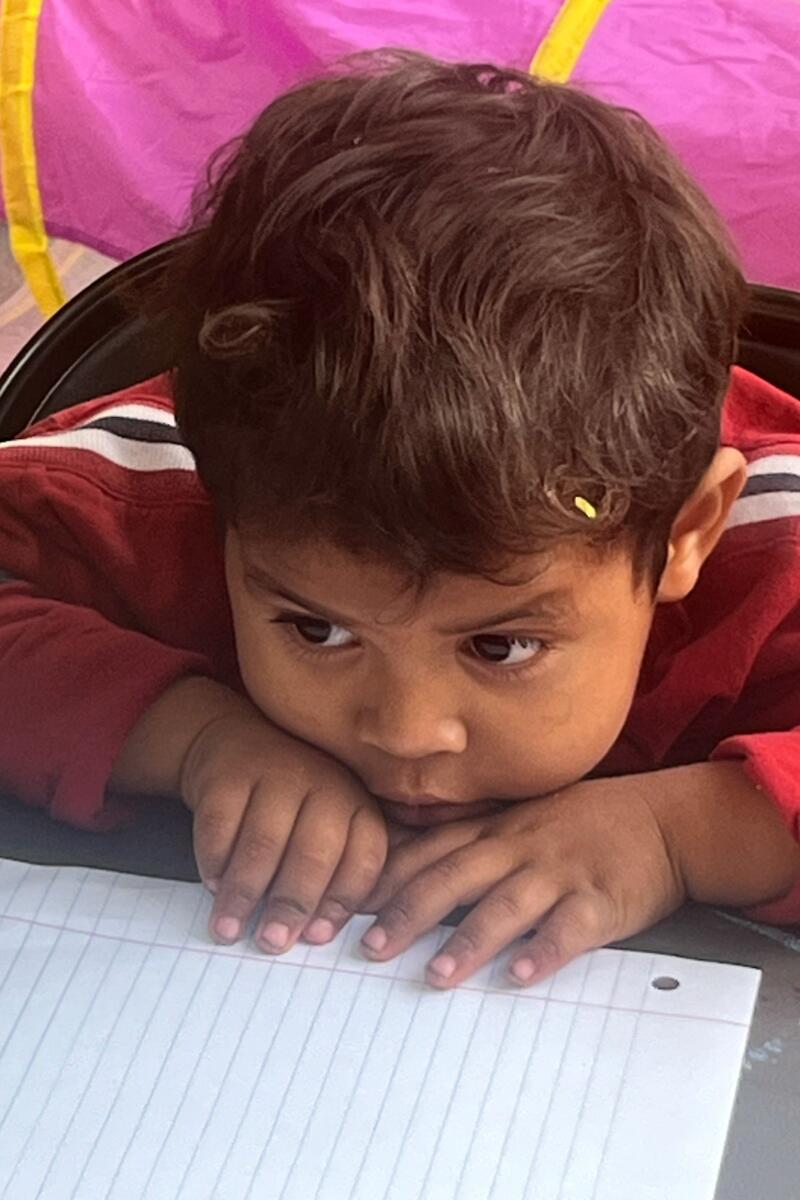

1. A young boy holds two soccer balls at Senda de Vida migrant shelter in Reynoso, Mexico. 2. A young child attends class at the Sidewalk School. (Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

“For some kids it’s recess. Fine,” Dallain said. “But if there’s a child in our program who genuinely is passionate about becoming the next Messi, I want them to feel like in our program they are actually developing and learning their skills. That creates hope of a child, right? It allows them to aspire beyond the confines of their shelter.”

Valeri García is one of those children. An undersized girl wearing an oversized pink Converse hoodie, a brown wool cap and a radiant smile, she skips into the safe space close behind Reyes, her enthusiasm infectious.

“She’s more active now; I don’t see her so down,” her parents say. “This is something to distract her mind, keep it busy.”

Under Reyes’ watch the 9-year-old runs through drills, plays tenacious defense — even taking a shot off her face — and tends to her sister Grace, not yet 2, who is wearing a second-hand Christmas sweatshirt and pajama pants beneath sad brown eyes and an expression stuck somewhere between curiosity and uncertainty.

Their father Reynaldo decided his family would have a better life in the U.S., but their three-week trek north from Guatemala ended here, just before Christmas. So they sit and wait for their turn to file an asylum application, their long-shot chances at a bright future having given way to the boredom, anxiety and fear of the present, all of which has been difficult for the girls.

“It’s just overwhelming,” Liliana Carlos, pastor of a Reynosa church who works with children in several shelters along the U.S.-Mexico border, said as she watched a soccer practice. “We’ve had children with suicidal thoughts. Everything falls on the children.”

A man doing laundry at the Senda de Vida shelter in Reynosa, Mexico.

(Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

Carlos sees her past in many of the children’s future. She was just 7 when she was taken across the border by a mother fleeing domestic abuse, only to be deported 20 years later to a country she didn’t know, beginning a quick spiral into drug and alcohol addiction.

“As a child, I did not ask my mom to go to the United States,” said Carlos, whose daughter Kayleen is one of the iACT coaches. “The children … they’re the forgotten ones. We lose sense of who we are. By my mom saving my life, I lost my life.”

“iACT,” she added, “is a school of hope.”

Gabriel Stauring and Katie-Jay Scott, iACT’s founders, saw how soccer changed things for children whose lives had been put on hold for years in African refugee camps. The sport involves constant motion, so the children burn not just calories but also stress and anxiety. Stauring and Scott, a college player, long wanted to expand their work to northern Mexico, but they were killed in a four-car accident 18 months ago, before that part of their vision could be realized.

However Dallain, who took over as executive director, saw that dream through with funding from Angel City, a professional women’s soccer team with a social conscience and a unique business model which dictates that 10% of the value of each sponsorship go directly to community impact work. The team has used that money to provide more than a million meals to people in need, perform nearly 10,000 hours of free youth soccer programming and award more than $134,000 in scholarships and grants.

1

2

1. Valeri Garcia, a 9-year-old migrant from Guatemala, smiles while playing in a soccer game at a shelter in Reynosa, Mexico. 2. Valeri and her sister, Grace, not yet 2, pump soccer balls before practice at an immigrant shelter in Reynosa, Mexico. (Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

Teaching the game to children in migrant camps certainly fit with that philosophy.

“ Working with a population in Mexico makes sense as really our first large foray into international impact,” said Catherine Dávila, Angel City’s head of community. “It’s much closer to home, it’s a population that has direct ties to our community here in Los Angeles. And then, of course, the fact that soccer is the lever. That’s totally spot on for us.”

The team’s initial agreement was to support the program for a year, which included a fact-finding tour to the border to find suitable partners, the purchasing of equipment and salaries for the four coaches. Dávila said the investment was in the “high five figures” and said Angel City intends to extend the funding for at least another year.

“For us, it moves well beyond the political stance. It’s a question of humanity. And these are human beings,” Dávila said. “Regardless of any political stance, they’re human beings. And recognition of that and helping people gain some sense of agency and humanity, that is always worthwhile.”

Angel City’s support has gone beyond writing checks. The team also donated shoes and other equipment to the kids and coaches in the Reynosa shelter, did fundrasing for iACT and discussed sending a delegation, including players, to the shelter this year.

“Angel City, from the beginning, has been incredibly supportive and open-minded,” Dallain said. “Not everyone has an interest and a heart for supporting these communities at the border. And they said, ‘We’re with you.’”

Now Dallain wants to expand iACT’s work to Matamoros, where the winding Rio Grande separates Mexico from Brownsville, Texas, at the eastern edge of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas.

The four-lane highway that covers the 57 miles between Reynosa and Matamoros, Tamaulipas’ two largest cities, is as flat and straight as a butter knife and it slices through an area contested by drug cartels and patrolled by Mexican army vehicles full of grim-faced soldiers and topped by mounted 50-caliber machine guns.

In Matamoros, iACT is partnering with, and learning from, Rangel-Samponaro and her Sidewalk School.

The school’s building is neat and festive. A children’s play area is decorated with balloons, paper streamers and colorful art projects taped to the walls. Paper flags of the U.S., Mexico and Venezuela cover a dry-erase board.

A block away, one of the largest and most notorious migrant camps, one which sprawled for hundreds of yards along the southern bank of Rio Grande and, activists say, was under the sway of the drug cartels, mostly has emptied. Left behind among the piles of trash are clotheslines made from barbed wire.

Outside, in the airy courtyard behind the Sidewalk School, seven children study under the direction of two teachers, both of whom also are waiting for their asylum petitions to be heard. The school week includes lessons in math, English, history and science, but there is also time dedicated to emotions and the passing of the “feeling stick,” which allows children a place to share their fears and anxieties.

Children attend class at the Sidewalk School in Matamoros, Mexico.

(Kevin Baxter / Los Angeles Times)

“This is so aligned with our mission,” Dallain said. “There’s so few organizations doing consistent work here that it just made sense for us to come.”

A battered blue pick-up truck ferried Dallain and two iACT coaches to a shelter on the grounds of a shuttered hospital to scout for a space big enough for a child’s soccer pitch. The overcrowded Casa Migrante Matamoros is less a shelter than it is a temporary city, with tiny tents aligned in neat, endless rows. More than 2,000 asylum seekers, about 20% of them children, live there.

“And there’s more coming. There’s always more coming,” said Victor Cavazos, who left the Coast Guard six years ago to work on immigrant-rights issues at the border.

In one corner of the shelter a group of kids plays under a trio of leafless trees on a small, bumpy dirt lot bordered on three sides by squat, sand-colored concrete buildings. It’s far from perfect for a soccer field but there are few other options and the need for a program like iACT’s is obvious. Dallain is optimistic.

“It’s been a lot of improvisation, flexibility,” said Cavazos, a Sidewalk School director. “It’s seeing the needs and addressing the needs.”

But it’s also about simply being there. Many of the people Stauring and Scott met when they first rolled a soccer ball into a refugee camp in Darfur are still there and so is iACT. There’s no telling how long migrants will be lining up by the thousands at the U.S.-Mexico border, but Dallain, who knows well the story about the little girl who used to greet Rangel-Samponaro at the border bridge, wants iACT to have the same impact here as it does in Africa.

So as long as there are children stranded at the Mexican border, she promises there will be soccer games to play.

“We always want the children to know that they can rely on this program. That’s one little bit of certainty we want to provide them,” she said.

“Every time I come here — I’m going to get emotional — but seeing the amount of joy the children were having, just the camaraderie, how they were excited to just even stand in line and do the drills. To me, that spoke volumes.”