Paris, France On a Saturday in late April, several dozen people gathered on the Pont d'Austerlitz bridge over the Seine River, shielded by scarves, hoodies and umbrellas as a light rain continued to fall.

Some held signs and banners demanding “Justice for Amara” and others that read “Amara is the victim of serious safety violations at the site by her employer.”

The rally in Paris, organised by the General Confederation of Labour (CGT), one of France's largest labour unions, was in memory of Amara Dioumasy, who died on June 16, 2023, while working as a construction supervisor on the Austerlitz reservoir, which was designed to improve the water quality of the Seine.

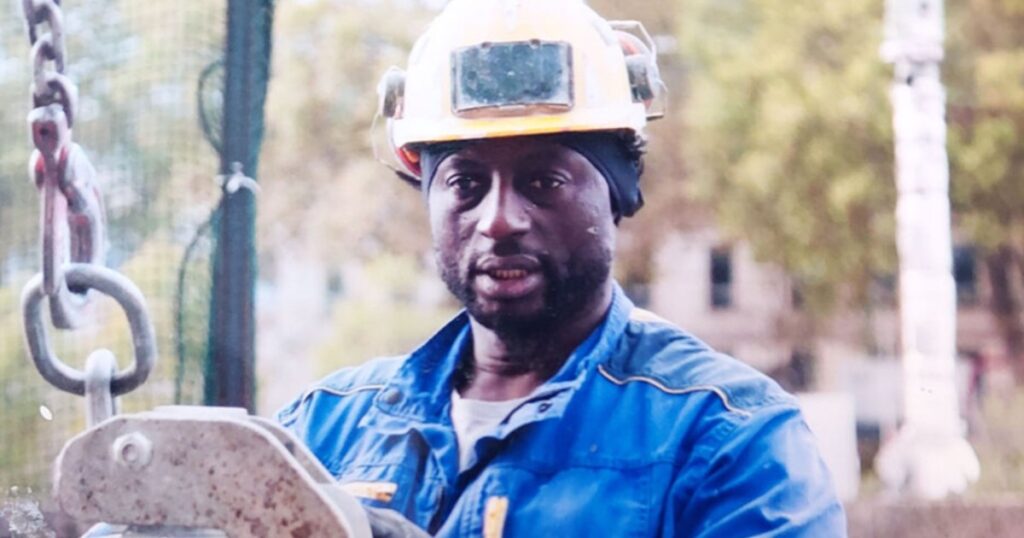

Dioumasy, a 51-year-old Mali native and father of 12, was hit by a truck near the end of his shift.

“We organized this rally to honour our brother, comrade and colleague,” said Leath Shuai, CGT union representative at Sade company, which employed Diumasy.

“There were serious safety issues. There were no crossing signs, no traffic flow, poor visibility and the trucks didn't honk their horns when backing up. There was no one to direct the trucks,” he added.

Choai visited the scene after the tragedy.

“I met a young man who told me that Amara was one of the first people to arrive on the site on the morning of June 16. He bought a bag of pastries to distribute to all the workers, encouraging them to take more than one,” he said.

“Amara's colleagues had tears in their eyes when they told me this story. Amara was always smiling, kind and generous to the people he worked with and his friends. He was a force of nature, but there was always a kindness in his face and he was always looking out for people. His family also told me that he was always someone his siblings could confide in, chairing family discussions and looking after everyone in Mali.”

The 100 million euro ($109 million) Basin d'Austerlitz project aims to capture storm and wastewater and prevent it from flowing directly into the Seine, according to the mayor's office.

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo approved a request to erect a memorial to Dieumacy near the spot where he was killed.

The city of Paris announced that an alley in Place Marie Curie will be named after him.

Cleaning up the Seine has become one of the pillars of President Hidalgo's second term.

The city has promised that the Seine will be clean enough to host open-water swimming and triathlon events during the 2024 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games.

“Because of the Olympics, there were deadlines for certain construction sites, like this one, with the goal of making the Seine more swimmable for the Olympics and events that were coming up, so there were deadlines, stress and pressure on the workers,” Ries said.

Many of the city's big projects for the Olympics, such as cleaning up the Seine, require labor costs.

Infrastructure projects are outsourced to large construction companies with varying levels of labor law enforcement. At least 181 workplace accidents have occurred on Olympic construction projects, 31 of them serious, said Nicolas Ferran, director of Solideo, a publicly funded company set up to build the permanent facilities that will remain after the Games end.

Accidents and labor rights violations are not unique to Olympic construction, but with the pressure to complete everything by the tight deadlines set for the Games, safety may start to be neglected.

It's a trend that Jules Boykoff, researcher and author of “Power Games: A Political History of the Olympic Games,” has observed across multiple venues, including London and Rio de Janeiro.

“When it comes to cities, the Olympics often act as a parasite, imposing various demands on cities, including deadlines that the Olympics automatically bring,” Boykoff told Al Jazeera.

“When there is a deadline, like for example the construction of the Olympic Village, all the possibilities for corruption come into play. All the possibilities for exploitation of workers by the IOC, a parasitic organisation, to meet an external deadline. [International Olympic Committee]. “

Ahead of the Games, the Paris 2024 Organising Committee and its partners have developed a Social Charter containing social, economic and environmental objectives, which was signed by trade unions and employers' organisations on June 19, 2019.

The Charter pledged to “combat illegal labor, anti-competitive practices and discrimination, monitor working conditions and limit precarious employment.”

“The Olympic Charter has made it possible, despite all the difficulties, to reduce the dangers on construction sites, even if everything is not perfect, because it improves traceability,” Gerard Le, the CGT’s federal secretary for migrant workers’ rights, told Al Jazeera.

“Because we have multiple subcontractors, inevitably some of them worked with undocumented workers. But having this charter and a diverse and representative organizing committee helped to mitigate any potential impacts.” As part of the charter, much of the construction of the Olympic venues is being led by SOLIDEO. But the Bay of d'Austerlitz project was not part of this group.

“In the SOLIDEO project, there were more regulations and more respect for the work,” Re said.

This additional pressure has exacerbated ongoing challenges, with more than two workers dying on average on construction sites in France every day, according to a latest report from France's National Health Service.

“The Olympics tend to magnify social problems and social challenges that already exist in society,” Boykoff said. “There's a clear track record, a clear Olympic trend, of Olympic host cities seeking the support of undocumented immigrant workers, who unfortunately often have little clout in society and are exploited through these relationships.”

France has the fourth-highest worker fatality rate in Europe and the highest number of reported workplace accidents of any European Union member state, at 560,000 in 2022, according to the health insurance report.

“France has been undergoing cuts to public services for many years, and labour inspectorates are no exception. As a result, there is a severe shortage of labour inspectors to check whether companies comply with the rules on working conditions. There is also a shortage in terms of legislation, especially when it comes to undocumented workers,” Le said.

He added that between 50 and 60 percent of construction workers in France are immigrants, many of them illegally.

In October 2023, more than 500 undocumented workers from 33 companies working on Olympic construction projects went on strike, refusing to return to work until they had proper immigration papers and legal work rights in France. They rallied at the Arena de la Chapelle construction site and threatened to occupy additional Olympic venues. As a result of negotiations, they succeeded in regularizing their immigration status.

France's strong history of trade unions has helped push through some changes, such as the Olympic Charter.

“What really struck me in Paris was the power of the unions and how they have tried to use the Olympics as a source of influence,” Boykoff said. “The more smart and organized workers there are, the more likely they are to use the Olympics to their advantage.”

But the union is still calling for improved working conditions. Asked what they wanted to change at the rally, Shuai said the union wanted justice.

“We want justice for Amara. Justice will be achieved if the management of the multinational company in charge of the construction project is held accountable for the lack of safety measures,” he said.