Boxing is a whimsically old-fashioned sport. Feuds are settled in fights, traditions are revered, and ageing faces run the show.

Fifty years since their heydays promoting Muhammad Ali, the 92-year-olds Don King and Bob Arum remain leading powerbrokers. They work with overlords who operate in the shadows. In this world, oversight is resisted and new tech greeted with suspicion.

At world title fights, judges still fill out scorecards on scraps of paper. They follow four extremely subjective criteria: “effective aggression,” “ring generalship,” “clean punches,” and defence. All these concepts are open to interpretation. Inevitably, they frequently create controversial decisions.

The problem extends to the sport’s top analytics tool. Despite the futuristic sheen of the CompuBox name, its stats are manually created by two people tapping keys when they see punches. The potential for biases and errors is endless.

TNW Conference 2025 – Back to NDSM on June 19-20, 2025 – Save the date!

As we wrapped up our incredible 2024 edition, we’re pleased to announce our return to Amsterdam NDSM in 2025. Registration now!

Fans and fighters alike have decried the results for decades. One of them is Allan Svejstrup, a Danish machine learning engineer. But Svejstrup (pronounced Svar-strop) also had an idea for a solution: computer vision.

A boxing aficionado with a PhD in maths, Svejstrup had his brainwave while working at a startup in China. “I also had the CompuBox doubts,” he tells TNW on a Zoom call from the Chinese city of Shenzhen. “I realised I could build a better system myself.”

He began to train an AI model on real boxing footage. The model then tracked not only the number of punches but also their impact, the fight’s flow, and each boxer’s movements.

Svejstrup was impressed by the early tests. In 2022, he turned the passion project into a startup: Jabbr.

Two years later, his brainchild had evolved into a fully-grown product. In the new boxing mecca of Saudi Arabia, Jabbr received a showcase during a fight for the heavyweight championship of the world.

But before arriving on that grand stage, the company had bouts to win outside the ring.

Hard knocks

Boxing presents big barriers to AI analysis. One emerges when evaluating punches and ringcraft, which are far harder to measure than, for instance, baseball pitches or golf shots.

“I understood why nobody else had done it successfully,” Svejstrup says. “The standard off-the-shelf tools that machine learning engineers use for soccer or basketball don’t work very well for combat sports.”

Another problem is the visual phenomenon of occlusion.

In computer vision, occlusion occurs when one object conceals the view of another. It’s rarely an issue when evaluating a tennis shot or home workout (as I know from personal experience). These applications can rely on off-the-shelf products that are fine-tuned on sports data. For boxing, however, they’re ill-fitting tools.

Occlusion is particularly troublesome when fighters get close and trade body shots. From one angle, a powerful body shot could be hidden and misclassified as missed. Jabbr’s solution combines multiple cameras with a novel approach to visualisation. Svejstrup named the system DeepStrike.

To interpret human movements, computer vision software typically converts video of people into stick figures or mesh representations. AI then learns the correlations between the physical movements and sporting actions.

It’s an approach that’s often effective. But boxing requires a greater depth of perception.

The sweet science

By building his system from scratch, Svejstrup sought to fill the gaps left by off-the-shelf software.

“Now, the downside of this is there are tonnes of technical problems to solve,” he adds. “And when you train an AI on something so complicated, you need huge amounts of data.”

For DeepStrike, that meant ingesting millions of punches. Jabbr found them by harvesting footage from the internet.

From the pros to amateurs, classic bouts to gym sparring, and 4K film to grainy clips, the videos captured diverse nuances of the sport. Boxing performance analysts then watched the clips in slow motion and tagged the data with their evaluations.

As their workloads grew, Jabbr needed to add new experts to the team. They arrived after a $750,000 seed funding round last year expanded the talent budget.

The team of analysts has now assessed over 250,000 punches. Svejstrup reckons they’ve spent 20,000 hours preparing training data for Jabbr’s proprietary model. By embedding their expertise, they teach the system to mimic their work.

After learning the ropes, the system heads to the ring.

Fight night

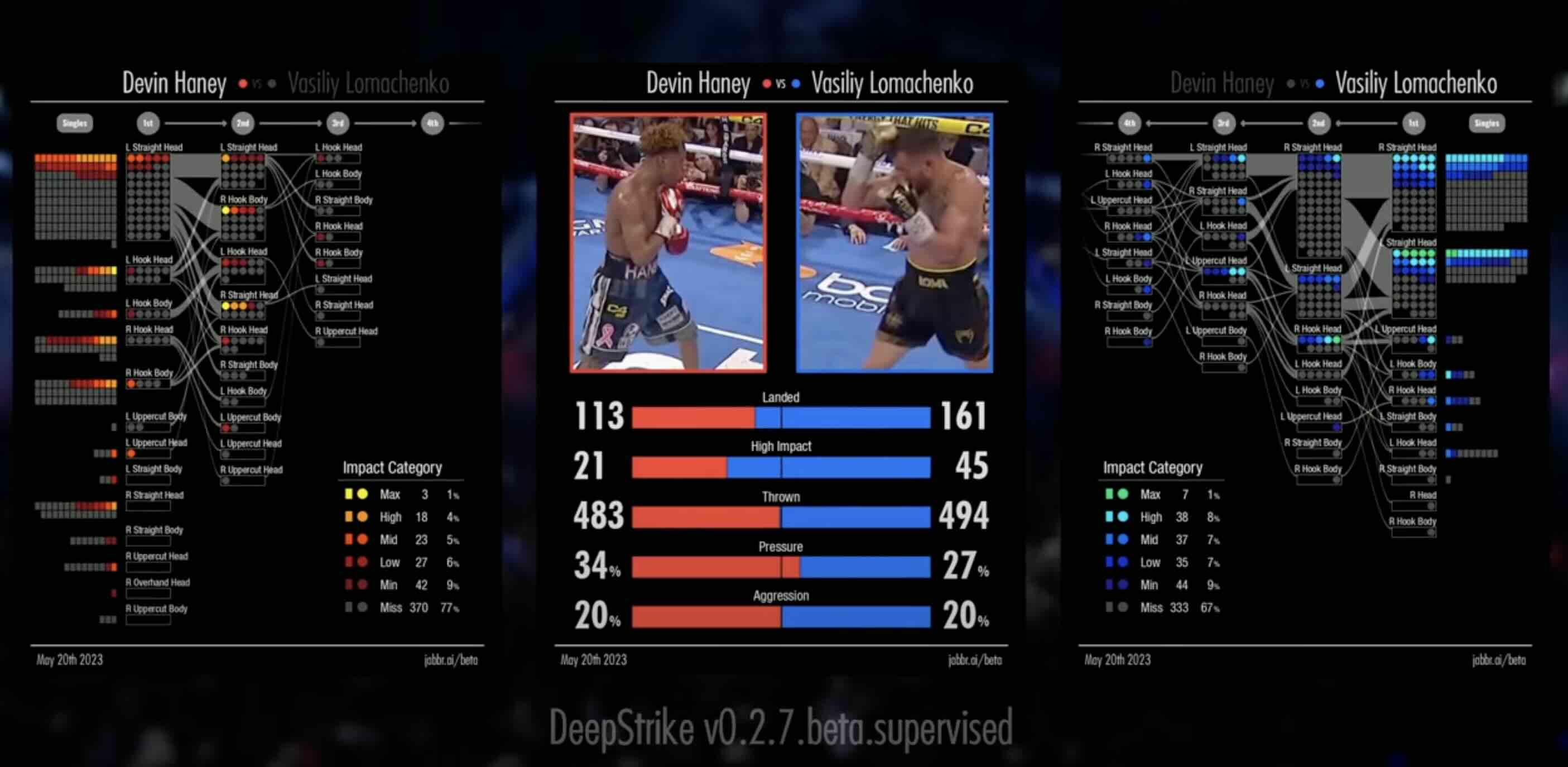

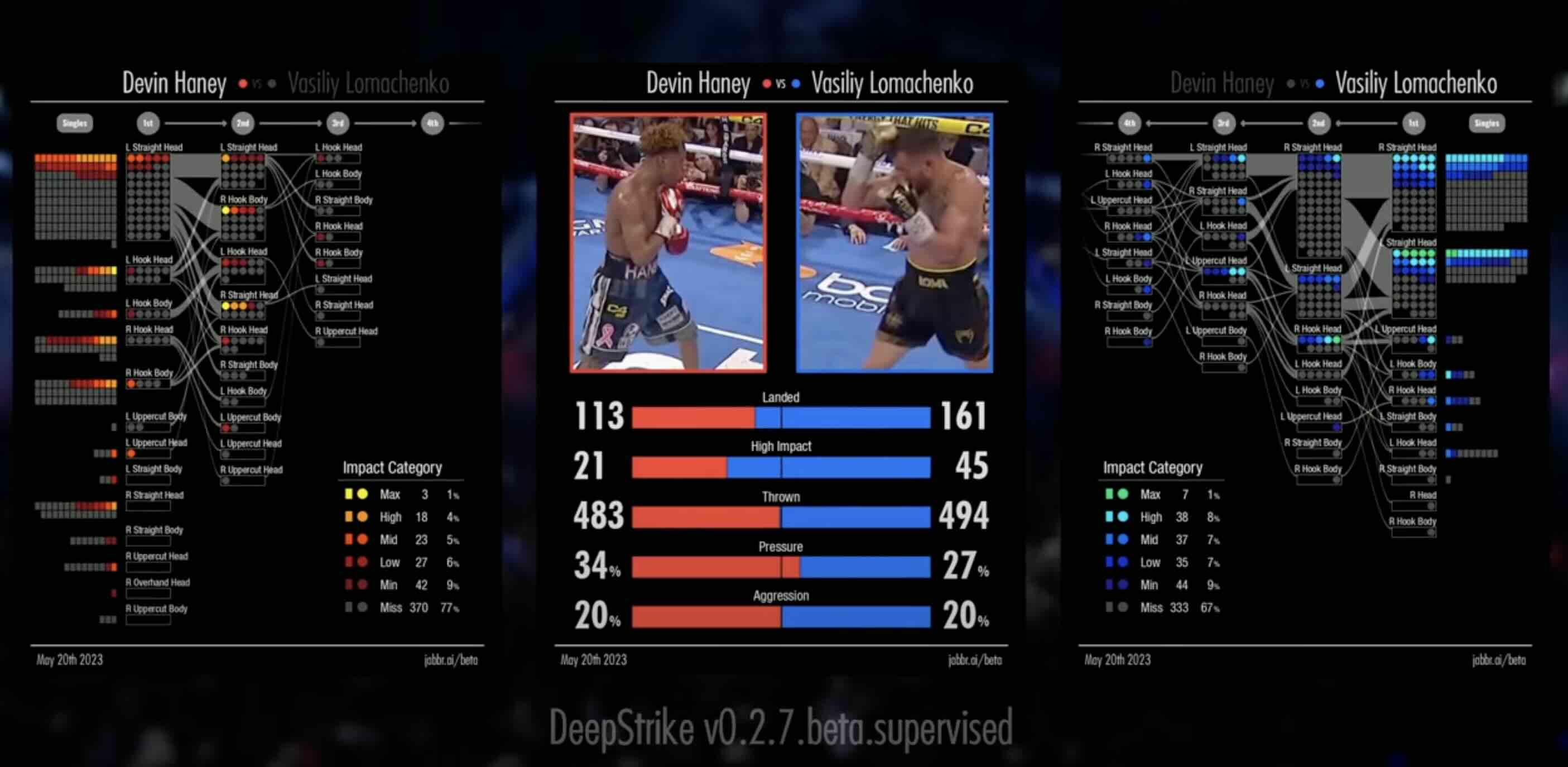

As soon as the bell sounds, DeepStrike gets to work. By the fight’s end, the system has measured millions of data points.

All this information is funnelled into 50 metrics for each boxer. They cover the punch numbers, the types of strikes, and various fighter movements. They also measure the impact of each blow, based on the cleanliness of contact and the visible effect on the opponent. Intriguingly, they even quantify those subjective judging criteria.

For effective aggression, Jabbr analyses efforts to hurt an opponent. DeepStrike detects this through three measurements: throwing punches with a high power commitment, initiating or ending exchanges, and volume of strikes. When a fighter triggers these indicators, they start a period of aggression. The final metric is based on the duration of these periods.

Ring generalship, meanwhile, is linked to pressure. Like aggression, this is defined by three indicators: moving forward while an opponent moves backwards, keeping the other boxer on the ropes or in the corner, and staying at mid-range or up-close without clinching. All these actions trigger the pressure metric.

CompuBox has no comparable depth or accuracy. Although the system is extolled on TV broadcasts, CompuBox only counts punches landed and missed. It then assesses their impact by dividing them into two crude categories: jabs (straight shots thrown from the lead hand) and power punches (everything else).

Jabbr, by contrast, quantifies the power and quality of every individual blow. Svejstrup estimates that the punch detection accuracy is 98 to 99%, while the punch classification is 95 to 99%. The precise percentage depends on the quality of the film — and the fight.

The view from ringside

Jabbr’s early experiments caught the eye of Radio Rahim, a pioneer of online boxing media. Rahim had built his career on digital platforms. His first steps came as a teenager training at the iconic Wild Card boxing club.

Rahim would film the fabled sparring sessions on the LA gym’s blood-stained ring. One captured a brutal brawl between American champion James Toney and Australian challenger Danny Green. The footage sparked a new craze for online “gym war” videos. It also sparked Rahim’s broadcasting career. He grew his brand on YouTube and later joined Jabbr in broadcasts from Saudi Arabia.

Long before those glitzy nights, Rahim had blasted boxing’s judging controversies and hostility to innovation. “Embrace technology?” he scoffs. “It’s still trying to embrace 20th-century tech, never mind the 21st.”

Rahim was similarly unimpressed by CompuBox’s limitations. Jabbr stood out as a promising alternative. Rahim joined the Copenhagen-based startup as an advisor and public promoter.

“The effect of a punch on a target is something that we’ve never been able to gauge mathematically before now,” he says. “It gives us not just a collection of numbers, but analytics that tell you what’s inside the numbers.”

Rahim wants Jabbr to shine a light on boxing’s shadier practices. “The most difficult problem in boxing is the idea that it’s corrupt. As much as I enjoy an MMA [mixed martial arts] night occasionally, it pains me to watch them surpass us with the new generation of fans, because it seems more transparent, they get the fights they want, and the right guy wins most of the time.”

MMA has also begun to embrace computer vision. Driving the uptake is another European startup, the UK-headquartered Combat IQ.

Combat models

Combat IQ was founded in 2022 by Tim Malik, a former professional scout in the Canadian Football League. Malik got the idea while watching the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) during the pandemic.

“I would wake up every week without fail and watch those fights,” he tells TNW. “I saw a major lack of data within combat.”

Combat IQ extracts this data from cameras positioned around the octagon. It also provides real-time fight predictions from the cloud.

The company has already established partnerships with MMA organisations, but Malik is also targeting boxing. “I like to say if somebody gets punched in the face we’re there to extract data,” he says.

That approach could create a competitor to Jabbr. But the two startups have very different business models.

Combat IQ focuses on delivering new experiences to viewers and odds to betting companies. “I’m here to make money, to be frank,” Malik admits. “I love sports, but at the same time, I want to build a sustainable business and do right by my investors. That means focusing on the aspects of sports that are profitable. And for me, that’s fan engagement and betting.”

Back to the gym

Jabbr has taken a different stance to Combat IQ. “Our primary target consumers are athletes and coaches,” Svejstrup says.

Svejstrup has shown Jabbr to boxers at the gyms where he trains in Shenzhen. “All the jaws just drop down,” he says. “That feels so different; it’s something millions of people care about.”

These people and places have become the focus of Jabbr’s plan. The startup will soon launch a commercial product comprising three cameras and an integrated timer unit. Users will not only access AI analytics. The “Jabbr Cam” will also provide automated media production.

This feature offers private clubs a simple and affordable tool to stream fights online. They can also generate highlights for each fighter in a social media-friendly format, alongside a full stats package.

“Because the AI already knows everything that’s happening, it’s not that hard to build an automated media production crew,” Svejstrup says. He plans to launch the system in September. Jabbr will sell the product at cost and then charge a subscription fee for the service.

“The benefit of the system is the speed and automation,” he says. “You get all these super detailed stats right away and you don’t have to pay a tonne of money.”

Last month, that speed was tested on the biggest fight in boxing.

From Shenzhen to Saudi

In the desert city of Riyadh, Jabbr debuted on the global stage. British broadcaster TNT Sports used DeepStrike during the historic bout between Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk. The showdown was the first undisputed heavyweight title fight for 24 years.

DeepStrike provided a user-friendly coverage enhancement. Unlike private gyms, TNT Sports required no extra equipment to install the system. The company simply sent its camera feeds to the cloud for AI analysis. The system then immediately returned the data.

As the fight progressed, Jabbr added extra insight to the broadcast. In the end, the judges awarded Usyk a razor-thin victory. Jabbr’s analytics suggest they got the right result — albeit by too narrow a margin.

The startup’s experimental predictions have also attracted attention. Before another heavyweight fight, DeepStrike indicated that Chinese colossus Zhilei Zhang would defeat the betting favourite Deontay Wilder. When Wilder was dominated and knocked out, the AI forecast was vindicated.

“When DeepStrike applies information about the impact of each of these punches landed, suddenly it can predict the results very, very well,” Svejstrup says.

Jabbr’s Saudi adventures have put the startup in the limelight. Turki Alalshikh, the mastermind of the kingdom’s boxing strategy, has shared the analytics with his 6.8 million followers on X. TNT Sports has also provided mainstream promotion for the brand.

Fans are now requesting new applications for the system.

Judge me not

Jabbr’s arrival has triggered calls for AI to replace judges. One viral moment arrived when Tony Jeffries, an Olympic medallist turned boxing influencer, touted DeepStrike as an alternative scoring system.

“That’s not the plan,” Svejstrup says. “Hopefully, it’ll bring some transparency to the sport and maybe even a bit of fairness when there’s a little bit of accountability there. But the real goal is to make this available to everyone.”

Broadcasters will nonetheless remain a target market for Jabbr. They can also provide powerful exposure — and not only for the startup. Radio Rahim wants them to also expose bad judges.

“The entire time I’ve been covering boxing, the lack of transparency has been like an albatross around our neck,” he says. “We’re now heading towards eradicating the subjectivity of what happened in the fight.”

For all the judges still scribbling scores on scraps of paper, Jabbr promises to not replace them. But their old-fashioned sport now faces ultra-modern scrutiny. Just wait till Don King and Bob Arum find out.