For roughly a century, until very recently, the Detroit Tigers centerfielder Ty Cobb stood as Major League Baseball’s unimpeachable career leader in batting average – at .366. Then, on May 29, baseball made a change and the “Georgia Peach” was … well, impeached.

In one of the more heartening and unprecedented steps in sports, MLB officials announced that Negro League statistics – carefully and meticulously researched and recorded – would immediately be incorporated into league canon. The decision thrust Josh Gibson – the transcendent Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays catcher and Negro Leagues pioneer of the 1930s and ‘40s – into the top spot among baseball’s all-time hitters (Gibson’s career average: .373), nudging Cobb to second and instantly erasing 100 years of history.

Or did it?

Although a welcome sentiment and a significant addendum to the record, MLB’s sweeping pronouncement does not change the past. Gibson, for all of his greatness, was for decades rendered a footnote and a tall tale by the white establishment. During his lifetime his stars were similarly crossed. In 1943, Gibson was diagnosed with a brain tumor but continued to play – and earn three more All-Star awards – despite recurring headaches and a worsening condition. In 1947 he died of a stroke aged 35, with only months between when he collected his last hit and when Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s race barrier. At Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Cemetery, Gibson was laid to rest in an unmarked grave.

As Larry Doby, the first Black player to join the American League, told his biographer: “One of the things that was disappointing and disheartening to a lot of the black players at the time was that Jack was not the best player. The best was Josh Gibson. I think that’s one of the reasons why Josh died so early – he was heartbroken.”

***

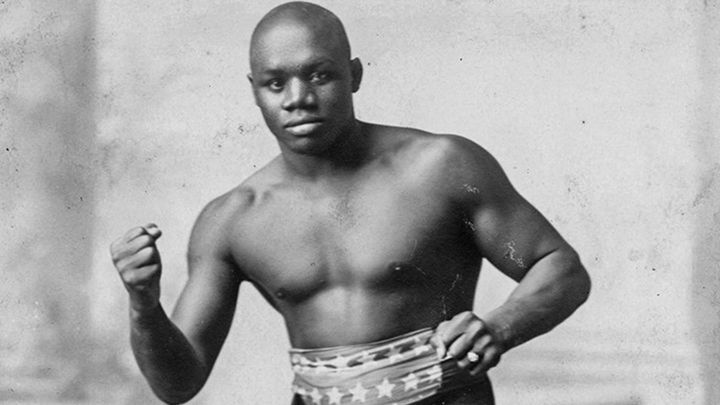

Given that MLB’s announcement roughly coincides with boxing’s recent hall-of-fame weekend and the anniversary of the death of Jack Johnson, the moment seems as appropriate as any to reconsider the ledger, and to identify some of the best fighters whose careers were irrevocably altered by the stormy racial climate of their times.

It was Johnson, Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali who most famously battled, each in his own way, widespread racism and the white establishment as fighters in their respective eras. But today all three are deservedly hailed and etched into boxing’s collective consciousness within their proper context. There regardless remain other fighters whose experiences with discrimination were so cutting and ill-fated that their careers, lives and legacies were fundamentally diminished for it.

Larry Gains (117-22-5)

Active: 1923-1942

Separating the facts about the historical figure from what we know of Larry Gains through Ernest Hemingway’s “A Moveable Feast” takes a bit of doing, but that speaks more to the writer’s ego and embellishments than anything else. There is plenty we do know about Gains, whose grandfather had arrived in Canada via the underground railroad after escaping slavery in Virginia, and who grew up in Toronto idolizing Johnson.

Although Gains didn’t begin boxing seriously until aged 20 he was a quick study who soon became Canada’s amateur champion and the first black boxer to fight in London’s Royal Albert Hall. Thus began a boxing odyssey that would provide Gains a modest level of fame and wealth in Europe, where he won the Commonwealth (1931-34) and world colored heavyweight title – of which he was the last holder. Although Louis would render that title obsolete when he became world heavyweight champion, it was Gains who first beat Germany’s Max Schmeling – as well as Primo Carnera, in front of what was then the largest crowd to ever attend a fight in Britain. Yet Gains, neither before nor after, got his shot at the proper title.

Joseph Dorsey Jr. (28-9-1)

Active: 1951-1969

Dorsey may not have been a world beater, and likely would have remained a regional fighter in the best of circumstances, but his story is no less important. A native of New Orleans, he grew up during a time of racial segregation. Those restrictions extended to boxing, at least up to a point. After George Dixon, the first black fighter to win a world title, battered amateur champion and Irishman Jack Skelly at the Olympic Club in 1892 to earn his second belt, the reaction of the white public prompted fight makers to schedule no more interracial fights at the venue.

Boxing in New Orleans wasn’t officially segregated until 1950, when Louisiana governor Earl Long signed a law banning mixed fights, among other activities. In 1955 Dorsey sued the state and the Louisiana State Athletic Commission, whose discrimination was deemed unconstitutional – but not until more than three years had passed – and then in 1959 an appeal was shot down. In the end Dorsey was blackballed and spent much of the rest of his life working as a longshoreman.

Panama Al Brown (128-19-12)

Active: 1922-1942

Born in Colón, Panama, Alfonso Teofilo Brown was the son of Horace Brown, an emancipated slave from Tennessee. Having been drawn to the boxing competitions of American soldiers while working in the Panama Canal Zone, the younger Brown soon learned that he had the gift himself, won a national amateur championship, and in 1923 stowed away on a ship to New York, where he quickly rose to prominence as a fighter. Within a year, Brown – at nearly 6ft tall and almost impossibly thin – was rated The Ring Magazine’s number-three flyweight in the world.

By 1926 Brown was taking fights at Madison Square Garden, but – as not only a black person and an undocumented immigrant but also a gay man – he otherwise faced layers upon layers of discrimination. Having been tossed from his gym and hotel, and with the scales tilted against him in matchups against white fighters, Brown traveled to Europe seeking acceptance and opportunity, and settled in France. The move launched his career, leading to a fight back in New York against Kid Francis, whom Brown upset to earn the NBA bantamweight crown and become the first Latin American world champion. Within a month, without explanation, the NBA stripped Brown of their title.

Brown experienced momentous highs, including stopping Gustave Humery in five seconds with a jaw-breaking right hand and whipping Gregorio Vidal to win the NYSAC world bantamweight championship. In more than 150 career fights he was never knocked out. But the lows were defeating – he faced racist mobs and was once poisoned before a fight. He was haunted by his mother’s death; he suffered with syphilis; and alcohol and opium were his regular companions. Brown moved back to France and won another title in a career last act that was guided by his manager and lover, the French poet Jean Cocteau, who once described the fighter as “a poem in black ink”. In retirement addiction eroded what was left of Brown’s shaky health, and his circumstances grew more dire and isolated until, in 1950, he was found unconscious on a New York street corner. Six months later, he died of tuberculosis.

Charley Burley (83-12-2, 50 KOs)

Active: 1936-1950

Eddie Futch called Burley “the greatest fighter” he ever saw. Archie Moore, the light heavyweight champ Burley toppled in 1944, called fighting him “inhuman”. A stylistic progenitor of Roy Jones Jr., Burley would stalk, slip and spirit around the ring, hands down and seemingly always a step ahead, before exploiting a weakness or springing a trap from a seemingly-impossible angle. A superb athlete, Burley was reportedly once offered a contract by none other than Gibson’s Homestead Grays.

Despite those laurels and Burley’s eventual induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992 you can be forgiven for never having heard his name. Invited to the 1936 Olympic trials he declined due to Berlin’s Nazi rule. After winning the world colored welterweight and middleweight championships, Burley was frequently ducked or passed over by world titleholders – including “Sugar” Ray Robinson – despite his being a ranked contender for almost a decade. He was left to compete in what amounted to a round robin of the top black fighters of the era – the unfortunately named “Black Murderers’ Row” – among whom Burley and Holman Williams were considered the finest. Burley’s skill, style and refusal to work with the mob soured his matchmaking prospects, but it was his race that ultimately relegated him – perhaps forever – to the status of “best fighter never to have fought for a championship”.

Joe Gans (147-10-16)

Active: 1893-1909

An orphan who began tagging along with his adoptive father to work at the Fell’s Point Broadway Market in Baltimore, Gans shucked oysters and was introduced to boxing by his boss there. He would eventually fight in local battle royals – grueling combat events featuring four or five black competitors, often blindfolded, hammering each other out until one remained – all for the entertainment of mostly white gamblers and spectators.

It was these and similarly problematic conditions that likely sharpened Gans’ wits and shaped his style. The “Old Master” was a slightly built strategist who often found himself stuck fighting larger men – and occasionally being outright cheated, by judges, referees and even his own manager. Gans may never have reached the position to compete for a proper world title if not for his status as a smaller black fighter making him less of a threat to the white public’s delicate sense of superiority. When he got his shot, against Frank Erne in 1900, Gans was cut over the eye and, fearing blindness, bowed out of the fight. Two years later he tried again, dismantling Erne to become America’s first black world champion.

Although Gans reigned for six years and would be regarded by Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleischer as the greatest lightweight boxer in history, he set off a firestorm with the triumph over Erne. Local newspapers undercut the accomplishment; Baltimore mayor Theodore Hayes attempted to ban interracial boxing in Baltimore in 1903, and the white public panicked. In July 1908, when Gans surrendered his title to Battling Nelson and lost again in the rematch two months later he was already being slowed by tuberculosis – a plague at the time that disproportionately struck Black communities in America. Two years later, at age 35, Gans became one of its casualties.

Harry Wills (70-9-3)

Active: 1911-1932

Among the great big men of the early 1900s who passed around the black heavyweight championship after Jack Johnson’s reign – including Joe Jeanette, Sam McVea and George Godfrey – it was Wills and Langford who were considered the best. Although Langford was past his prime through the period in which Wills dominated their rivalry, they split their first five fights (2-2-1) – and while Langford has a place in the top 10 of any credible list of all-time boxers, Wills is rarely mentioned as even one of history’s top 100.

Wills was a brilliant athlete – powerful and agile; standing as tall as 6ft 4ins – who bested all the black heavyweights of his era. In February 1916 Wills was knocked out by Langford. Wills’ fiancee Edna Jones was so disquieted by the loss and convinced that Wills’ career was over that she took her own life. Wills would return inside a month to easily outpoint Langford, the start of a 58-2-3 run – including an 11-0-1 record against Langford during that stretch.

When given the rare opportunity, Wills also showed his mettle against the top white heavyweights in beating Willie Meehan and Gunboat Smith, and drawing with Luis Firpo. But he was famously ducked by world champion Jack Dempsey – or at least his promoter, Jack Kearns, who didn’t want to risk a loss and a repeat of the race riots that followed Johnson ascending to heavyweight champion. BoxRec ranks Wills the number-one heavyweight from 1915 to 1917, and Wills wouldn’t lose for another five years after that. In 1922, a New York Daily News poll identified Wills as the fighter readers most wanted to see face Dempsey, and although a contract for a fight was signed, Dempsey’s side never moved forward. The New York State Commission took a stand and refused to sanction any Dempsey fight other than a defense against Wills; the champ simply traveled west to Philadelphia to take on Gene Tunney, and Wills’ last best chance to succeed Johnson as the world heavyweight champion slipped away.

Sam Langford (178-30-38)

Active: 1902-1926

The grandson of a former slave, Langford struck out from his native Weymouth, Nova Scotia, at an astonishingly young age – landing in Boston, where he began working as a janitor at a boxing gym and, at age 15, won the amateur featherweight championship. Although short (likely shy of 5-foot-7), he was long-armed, thickly muscled and brilliantly skilled inside the ring. His exact birth date is an open question, but Langford was indisputably precocious – especially by modern standards.

At 17 years old, Langford convincingly thumped lightweight champion Gans, but missed weight, denying him the title. Nine months later he bloodied and clearly beat welterweight champion “Jersey” Joe Walcott, but was saddled with a controversial draw. Aged 20 Langford took on world colored heavyweight champion Johnson, who – more experienced and 30 pounds heavier – outpointed Langford over 15 rounds. Langford chased Johnson for a rematch for years, overwhelming dozens of opponents in the interim, including the best black fighters of the day, as well as the top white fighters who were willing to fight him – Stanley Ketchel and Philadelphia Jack O’Brien among them.

But Johnson, who in 1908 won the world heavyweight championship, never granted Langford the rematch he had inarguably earned. Langford would go on to win the world colored heavyweight championship on five separate occasions and, during his peak years, decimated his competition across every division from lightweight to heavyweight. With 126 career knockouts “The Boston Bonecrusher” was ranked second on the list of greatest punchers of all time by The Ring Magazine. But in 1918, Big Fred Fulton – a 6ft 6ins puncher – landed a punch that severed the optic nerve in the left eye of Langford. His sight worsened, and in his later years Langford needed to be guided into the ring. In 1926, Langford – 43 years old and clinically blind – was stopped in the first round by Brad Simmons (15-8-2) in the sparse, fading oil town of Drumright, Oklahoma. Langford is still considered by many boxing historians to be the greatest fighter to have never won a world title.