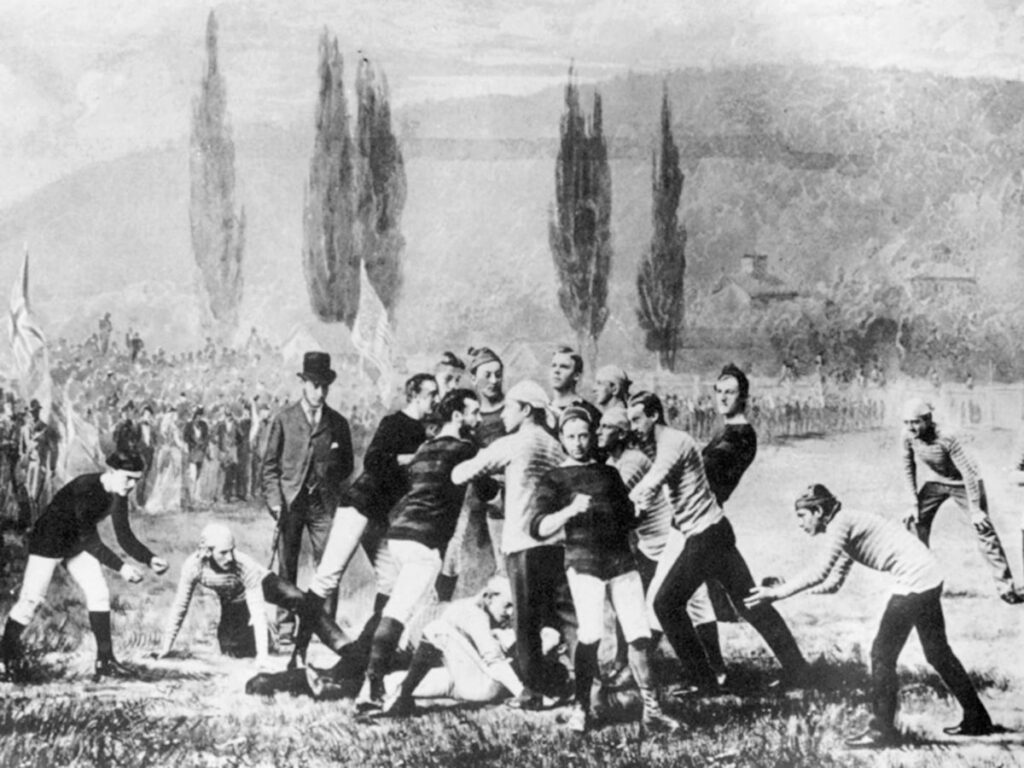

A composite image of a North American-style rugby football game between McGill University and Harvard University on October 23, 1874, depicting the first game of the sport played in Canada. In 1874, McGill University students challenged the Harvard University team to two games played in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on May 14 and 15, 1874.William Notman/Courtesy of McCord Museum and McGill University

Thirty-five years before the Gray Cup was first awarded, nearly a century before the Super Bowl was born, and long before the Super Bowl evolved into one of the most-watched sports on the planet, North America's first official game was played. It was done. A style of rugby football was being played on a field outside Boston.

150 years ago Tuesday, a crowd of about 500 people paid 50 cents each to watch the first of a two-day series of games between McGill and Harvard, each performing their own version of “football.” did. Harvard University played under its own “Boston Rules,” using a round ball and most similar to what is now called soccer in North America, while McGill University used its oval-shaped ball in the United States. Introduced the ball, and more importantly, the ability to pick it up. Get up and running with it.

As it turned out, McGill didn't win either game in 1874, losing 3-0 on May 14 under Harvard rules, and in a game played under McGill rules the next day. Both teams ended up in a scoreless draw. The third conference, held at McGill in the fall of the same year, was also conducted in Harvard fashion.

But more than just wins and losses, the contest marked a landmark moment for the continent's oval ball game, as it also marked the birth of a rugby rivalry that continues to this day. In retrospect, Harvard's Jarvis Field served as a metaphorical petri dish for the evolution of Canadian football, American football, and rugby, the most traditional of the three sports.

“All of our games start there,” says Steve Daniel, official historian of the Canadian Football League. “And it's, 'Hey, this is a lot more fun than soccer, a lot more fun than rugby union, it's a good game to play' because it's more open, it's more flexible.” Soccer Now Look how flexible it is.

“For me, that's the real significance of that event. That and the encouragement to create rugby football organizations in every province in every major city.”

From those games, Daniel explains, governing bodies such as the Canadian Football Association and the Canadian Rugby Football Union, as well as the Ottawa and Winnipeg football teams, were born.

“That to me ultimately is the historical relevance of this game and saying, 'This is a game worth playing.'”

South of the border, the game was well-received, with Harvard eventually adopting McGill's rules and incorporating them into their game against Yale the following year, and subsequently encouraging many other schools to embrace the fuss. I persuaded you.

As famed New York Times sportswriter Red Smith wrote in 1973, “Harvard and McGill University crossed rugby with a form of bloodletting called the Boston Game, creating what we know today. It created a collision sport.

But the 1874 contest was also a turning point for the sport of rugby on this side of the pond. The Canadian Rugby Football Union (now known as Rugby Canada) was founded in 1884, so it wasn't until 1932 that Canada officially hosted its first international test match.

“I think it was literally the first international game for Canadian Rugby that McGill played at Harvard,” says Ian Bailey, McGill's current head men's rugby coach.

Bailey, who has been the head coach at McGill University since 2013, said the games against Harvard are special and each game helps commemorate the first tournament dating back to 1874. But the pandemic halted the nearly annual convention, and his alumni base crumbled. get annoyed.

Last fall, he said, he was invited to attend the Rugby World Cup in France by several former McGill players who are now active in Europe. But the burning question they all had was when the school would put Harvard back on the schedule.

The answer is this fall, when the two schools meet at McGill to commemorate the 150th anniversary of their first meeting.

“We really want the event to live up to our 150-year history,” Bailey said.

The two schools have played rugby matches quite frequently since 1974, the 100th anniversary of their first meeting. At this time, the Cobo Cup was an initiative of Peter Cobo, a former men's rugby coach and engineering professor at McGill University, to draw attention and raise funds for the school's rugby program, which was struggling to survive at the time. was introduced. Covo passed away the year before, so he never got to see the fruits of his efforts, but the trophy will be awarded in his name and contested again this fall.

“At that time, it was a matter of life and death for the rugby program,” said son Ken Covo. “And I think that's what inspired him to come up with the idea of, 'Okay, here's a way to remind people that we're not just a bunch of people running around in a field.' ” There is a long history here, and in fact a very important history in terms of the role that McGill and Harvard played in getting football off the ground in North America. ”

None of McGill's current rugby players will be taking part in the competition as there has been a gap of five years since the last Cobo Cup competition, which McGill won 47-15. But that doesn't mean the two schools aren't heavily focused on their shared history, with McGill currently holding a 24-14 edge in the Cobo Cup matchup.

“I don’t think we necessarily feel it on a day-to-day basis, but when you have alumni come in and surround the event, you get to talk to them, find out when they played, and they see your play. You can tell how excited they are when they see it.’ You feel that connection somehow,” said current McGill rugby manager and former three-time Cobo Cup player Michael Modafferi.

“Playing McGill was always the highlight of the fall season,” said Andrew Pinkerton, a Canadian who captained Harvard's rugby team in the early 1990s. “The games are always very competitive. And whether it's having McGill in Cambridge or going to Montreal, we've always enjoyed the competition and the rivalry.”

Perhaps no one is better qualified to talk about the historical impact of this game and the rivalry between the two schools than Joseph Hannaway. The McGill graduate, who was a member of the school's 1955 national championship team, actually played on the football team during his first two years at the school. Known as “Toe Joe,” he became known for his kicking exploits and later moved to Harvard University to teach neuroanatomy, but his influence at McGill is still felt. The “Hannaway Award'' was created to be given to the player who set the best example two years ago. A gentlemanly trait, the rugby version of the NHL's Lady Byng Trophy.

“Harvard won two of the three games,” he said of the 1874 game. “But again, until the American Ivy League was established and various rules regarding the line of scrimmage and the passing of the ball were changed, Harvard University had no idea what the game was or how important that game was. I don't think you understood that.

“Neither side realized how important it was to both schools until many years later.”