“We have to recognize that unexpected succession is something that all democracies have to go through,” said Daniel Rogers, who has taught American history at Princeton University for most of his career.

Over nearly 250 years, American presidencies have come to premature ends several times, including four by assassination and, in the case of President Richard M. Nixon, by scandal. In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson, suffering the devastating consequences of the Vietnam War, shocked the nation by announcing that he would not seek or accept the Democratic nomination.

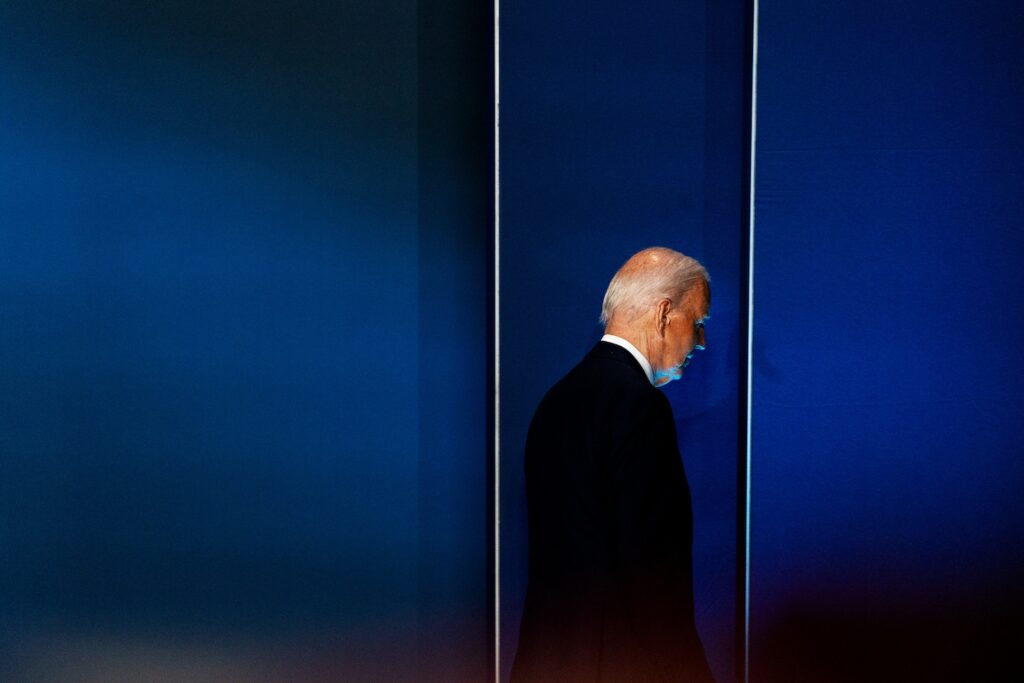

Biden succumbed to something more mundane: the decline of age and growing doubts among both sides after his lackluster performance in the June 27 debate. Party elites and supporters believed he could defeat former President Donald Trump and lead the country effectively. In the weeks following the debate, party leaders waged a relentless campaign. Ultimately, Biden believed it was best for the country to step down.

To Rogers, Biden's decision under pressure was historic and a sign that democracy is working as intended. “We should accept this as relatively normal,” he said.

Others echoed similar sentiments: “This is what political parties exist to do,” said Elliot Cohen, a historian and political scientist who recently retired from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. “This is not chaos.”

By forcing Biden to reveal that he no longer had the capacity to run an effective campaign, party leaders were sending a message that the American political system is bigger than any one leader. As Biden struggled for weeks to hold on to the presidency, he repeatedly argued that his first-term accomplishments proved he was uniquely qualified to lead the country.

“Name me one foreign leader who I don't think is the most effective leader in the world on foreign policy. Tell me. Tell me who it is,” Biden roared during a recent call with Rep. Jason Crow (D-Colo.), his tone echoing that of Trump, who has boasted that he alone can “fix” the country.

In a letter announcing his decision on Sunday, Biden listed his successes but also acknowledged that they weren't “my own” achievements, explicitly mentioning the political system he has sworn to protect as a candidate and president. “I know I could not have done any of this without you, the American people,” he wrote.

Historians hailed Biden's decision to leave office as an example of democracy at work, but there was widespread agreement that a president who promised to return America to a time of normalcy left behind a system of government that remains under heavy strain.

Polls show that trust in core American institutions like the Supreme Court, the military, the criminal justice system and Congress is near its lowest level in the last 50 years. Many Republicans and Democrats see this election not just as a contest for the White House but as an existential fight to save the country from annihilation at the hands of the other party.

For the first time in more than 50 years, the Democratic nominee will be chosen through a yet-to-be-determined process rather than an open primary by voters. Party elites appear to be moving quickly to endorse Vice President Harris as the best candidate to challenge President Trump, with most of the delegates who pledged to vote for Biden at next month's convention now pledging to vote for her.

The clearest historical parallel to the current situation dates to March 1968. Driven by anger over the Vietnam War, his own deteriorating health, and the possibility of a challenge from his fellow Democrats, Johnson decided not to run for a second term. He made the decision just before the primaries began. A few months later, in Chicago, mainstream Democrats chose Vice President Hubert Humphrey as their nominee over Senator Eugene McCarthy, an anti-war candidate who had broader grassroots support.

But there are also significant differences between the two time periods.

The upheaval of the late 1960s – mass protests, riots, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy – shook the foundations of American democracy. “People were talking about a revolution on the horizon,” said Rogers, the Princeton historian.

Rogers described the current climate as one dominated instead by resignation and cynicism: a “retreat of faith in the possibilities of democracy” reminiscent of the 1970s, when hyperinflation, crumbling infrastructure and rising crime rates seemed to overwhelm the country's leaders and political system. Rogers said such a climate still poses grave dangers to American democracy. He warned that this climate is particularly suited to a candidate who projects “the kind of strength, authority and a kind of dictatorial certainty that democracy cannot provide” — in other words, a candidate like Trump.

Other historians have taken a darker view, drawing parallels to the late 1850s, when the issue of slavery divided the country. “This was a moment when the country could no longer find a way to compromise,” says Nell Irvin Painter, another Princeton historian and author of “The History of the White Man.” “And so, as we all know, armed conflict broke out.”

Painter said the chances of armed conflict erupting again were low — the clear geographical divisions that led to secession and civil war no longer exist — but he spoke of a country similarly caught up in a struggle over two competing visions of American democracy.

Democratic leaders, including Biden and former President Barack Obama, have described America primarily as a set of beliefs and principles. In a 2022 speech at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Biden framed the country as “one idea, the most powerful idea in the history of the world.” It's a vision of a “nation in perpetuity,” in Obama's words, ever-changing, forever striving to realize the lofty ideals enshrined in the nation's founding documents.

In a speech at the Republican National Convention last week, Senator J.D. Vance of Ohio, Trump's newly announced running mate, rejected the Democratic view in favor of a more fixed, geographically defined vision of the country and its democracy. “America is not just an idea,” he said. “America is a people with a common history and a common future. It is a nation.”

In Trump and Vance's view, the greatest threat to American democracy comes primarily from within, in the form of Democrats and illegal immigrants who have “weaponized” the justice system to punish their enemies. “They're coming from prisons. They're coming from jails. They're coming from mental hospitals and psychiatric hospitals,” Trump warned last week as he accepted the Republican nomination.

There seems to be a consensus among voters of both parties that American representative democracy is not working particularly well in such a divided country.

A recent poll by The Washington Post and George Mason University's Schar School of Government found that majorities of voters in six battleground states that Biden narrowly won in 2020 said threats to American democracy were extremely important to them. But voters clearly did not think either Biden or Trump were uniquely capable of defending the country from those anti-democratic threats.

For Aziz Rana, a constitutional historian at Boston University Law School, widespread disillusionment with American democracy is the product of a system that regularly produces results that don't align with people's hopes.

This trend is most visible on hot-button issues like abortion rights and gun control, where lawmakers have done little to restrict access to firearms in an era of school shootings. On the abortion issue, voters in heavily Republican states like Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, Michigan, and Ohio have either rejected new abortion restrictions or supported more accessible measures by wide margins. But despite the will of the people, there is little chance that reproductive rights will be restored at the national level anytime soon.

Rana said the disconnect is reminiscent of the 1912 election, when a similar sense of disillusionment led to a four-party election for president featuring candidates from the Democrat, Progressive, Republican and Socialist parties. That election, won by Woodrow Wilson, resulted in two constitutional amendments that would forever change American democracy. The 17th Amendment established popular voting for U.S. senators. The 19th Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote.

Today, amending the constitution is nearly impossible.

Historians have described Biden's decision to step down as momentous and shocking, but not out of line with the natural functioning of American democracy. Instead, they have described Trump and the movement he leads as larger outliers.

For much of U.S. history, the major political parties touted a shared belief in “inspirational ideals” but differed about how to get there, said Abram Van Engen, a historian at Washington University in St. Louis.

For Van Engen, Trump has departed sharply from that tradition. The former president's vision of American greatness is defined not by lofty ideals but rather by the country's military might, economic power and ability to impose its will on its enemies. “He doesn't seem to understand American history or the arc of our story at all,” Van Engen said.