There is no particular reason for publishing for the second time this article, which was originally written and published five years ago on the website of the WBA, boxing's highest governing body.

The reason is that a few days ago, during a gathering with friends, someone commented that it would be a good idea to write something about “Mantequilla”, one of the best boxers in Latin American history, probably in the top 5 in the region, so this article is now expanded and republished here with new details.

The Cuban-Mexican boxer and boxing legend José Ángel Nápoles, better known as “Mantequilla”, died on August 16, 2019, at the age of 79, after suffering a heart attack during his final bout in Mexico City. Having suffered from various illnesses (diabetes, senile dementia, malnutrition), he died in the most pitiful and immense poverty.

Napoles is a former World Boxing Association and World Boxing Council welterweight champion and is ranked as one of the greatest champions in the 147-pound weight class and in boxing in general, with the prestigious The Ring magazine ranking him 32nd among boxing's 100 greatest fighters of all time in 2007.

Saying goodbye to Cuba in search of fame

Born in Santiago de Cuba on April 13, 1940, Napoles left his home country in the early 1960s after it was banned from professional boxing by Fidel Castro's revolutionary government in 1959, and he quickly became a Mexican citizen. By the time Napoles left, never to return, he had fought 18 bouts, winning 17, losing one by point, and knocking out six. He was already emerging as a promising prospect among a generation of great Cuban boxers that included Luis Manuel Rodriguez (then world middleweight champion), Douglas Vaillant, Angel “Robinson” Garcia, and Florentino Fernández. He was so named because of his cat-like movements in the ring, elusive and non-stop attacking, passing and blocking punches, and throwing explosive punches.

He made his debut in his home country in August 1958 against Julio Rojas (winning by first round KO) before suffering his first defeat to Hilton Smith in his eighth appearance. As mentioned above, he traveled to Mexico with a record of 17 wins, 1 loss and 0 draws at lightweight, and made his debut on July 21, 1962, accompanied by fellow countryman and journalist Cuco Conde, in Mexico City against Enrique Camarena, knocking him out in the second round.

When he first left Mexico City, he went to Venezuela, where he won more than 30 matches before knocking out American L.C. Morgan in the seventh round in Caracas on November 30, 1963. Seven months later, on June 22, 1964, he faced local idol and heavy hitter Carlos “Morocho” Hernández in Nuevo Circo in the Venezuelan capital, who would later become the first Venezuelan boxer to win the junior welterweight world title.

With similar records — 34-3-0 with 17 KOs and 34-3-3 with 22 KOs respectively — the 24-year-old Napoles and the 22-year-old Hernandez were expected to fight to the death, and that was indeed the case. Hernandez knocked Napoles down with a right-left one-two in the space of eight seconds in the fourth round, but “Mantequilla” quickly recovered, backing Hernandez into the ropes in the seventh round and unleashing a barrage of punishment. Referee Crispulo Salazar's intervention halted the carnage with a confused, staggering and defenseless “Morocho” still standing.

Shortly afterwards, “Mantequilla”, already world famous among Mexican and Caribbean lightweight boxers, recorded a long winning streak (decision losses to Mexicans Tony Pérez and Alfredo “Canelo” Urbina, and a 4th knockout loss to American LC Morgan). On April 18, 1975, at the Forum in Inglewood, California, he faced WBA and WBC champion Curtis Cokes, defeating him in the 13th round after a hard-fought fight. Two months later, he defeated Coke again in the 10th round. He then successfully defended the title against Emile Griffith and Ernie Lopez, but in December 1970, Billy Backus (nephew of the famous Carmen Basilio) took Coke's belt in the 4th round. Six months later, in a rematch, Coke won in the 8th round.

An Unequal Battle Against the Monsoon

He went on to win consecutive bouts over Hedgemon Lewis, Ralph Charles (seven times), Adolph Pruitt (twice), Ernie Lopez (seven times), Roger Menetley, Clyde Gray, Lewis (nine times), Argentina's Horacio Saldaño (three times) and Azteca's Armando Muniz (twice on points), for a total of 15 exhibition bouts, eight of which were won by knockout.

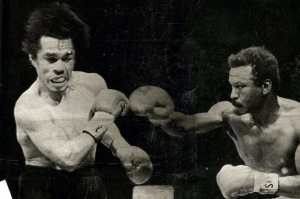

In the midst of those bouts, he faced the legendary middleweight champion Carlos Monzon in Paris (February 9, 1974, half a century ago). It was an unequal duel, because the southpaw (159.9 lbs. vs. 153.8 lbs.) Monzon had the advantage in punching power and reach. Paradoxically, the bout, which ended in Monzon's disadvantage, became the most watched and memorable bout in Naples between the two legendary fighters, for fans all over the world. The powerful Argentine fighter won in the seventh round, but Naples never looked back. He later accused Monzon of digging the thumb of his glove into his eye. Of course, the accused denied the words of his defeated rival.

On January 8, 1995, 11 years to the day after that bout, Argentina's greatest fighter of all time was killed in a car accident while returning to the prison in his hometown of Santa Fe, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for the violent murder of his wife, Alicia Muniz.

“Manteca”, as the Mexican press called him, fought four more bouts after Monzón (against Ruiz, Saldaño and Muniz twice) before fighting for the double crown against the Englishman John Stracey on December 6, 1975, at La Monumental bullring in Mexico City. After 17 years of constant activity, the aged and exhausted warrior of 35 years laid down his weapons at 2 minutes and 30 seconds into Chapter 6. He never fought again. His record reads 81 wins (some publications say 77), 54 by knockout and only 7 losses (only 4 of which were before the limit and no draws). He was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1982 and the International Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York in 1990.

After his retirement he lived a bohemian life, gambling and even co-starred in a movie with Aztec wrestling idol El Santo. The money he made from gloves quickly disappeared and he fell into extreme poverty, surviving only with occasional help. Nearly five years ago, as the poet says, he set off on his eternal journey, light-heartedly, without a penny in his saddlebags and living as a renter in Ciudad Juarez, albeit a glorious millionaire. He was truly a great man among great men.