Growing up in Northern Ontario, Brock McGillis' life was all about hockey. Comparing it to football in the UK, he explained to Attitude magazine, “Hockey is a way of life. It's part of our culture and our history.” Brock was obsessed with the sport. “I lived really close to the arena and every day after school I went there hoping to get on the ice. My parents delivered all my meals to the arena on the weekends. I just lived there. I loved it.”

At age six, Brock realized he was gay. He discovered it while watching a movie with his parents. Seeing a gay character on screen, he said, “What a nice guy.” His parents' response was amazing: “If you're gay, that's gay. You're Brock. We love you.” But in the culture Brock grew up in, it felt impossible to be both a proud gay man and a professional hockey player. “I had a really hard time hearing homophobic slurs every day, so I just suppressed it.”

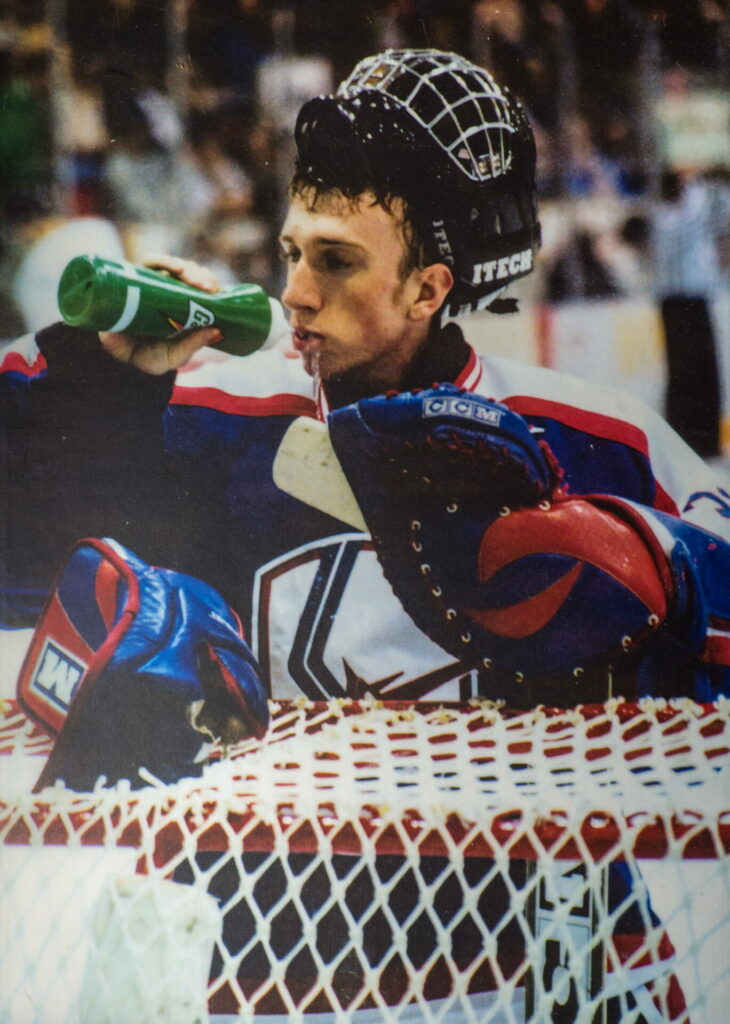

Bullock jokes that he's a good actor for maintaining such an overbearing mask. The ice rink provided relief from the fire that was burning inside. He continues: “Once I left the locker room and was a goalkeeper, nothing else mattered. Everything went away. It was my way of not facing who I was. But I hated everything that led up to it – the bus rides, the locker rooms, team dinners – because I was sitting there wishing I wasn't alive. There were times when I couldn't play the part, and I knew people knew I wasn't me. It was hard.”

“I couldn't sleep, I was depressed, I had suicidal thoughts and my career started to go off the rails.”

A talented hockey player, Brock played for the Windsor Spitfires and Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds of the Ontario Hockey League. He then played for the Kalamazoo Wings of the United Hockey League. He soon became a draft candidate for the National Hockey League. During that time, Brock blended in with the group. “I took the stereotype of a hockey player to the extreme. I'm embarrassed to admit this, but I was a womanizer. I walked into rooms like I was a gift to the world. I walked around the mall signing autographs. Everyone thought I was living the best life I could, but I never expected to go home and cry. I hated myself. I wanted to die, and I came close to dying many times.

“By the time I was 18, I was drinking heavily. I was drinking every day from 18 to 23 and had a season-ending injury every year. I was having trouble sleeping, I was depressed, I was suicidal and my career started to go off the rails. I was supposed to be on a linear trajectory. I was 23 and still suppressing my sexuality and I just sat down,” he said. At the time, he was playing for Duindam Wolves in Europe. “I knew two things were going to happen. One, my career was over. I was already going off the rails. And two, and most importantly, I knew if I didn't figure out who I was, I was going to die. So I went back to Toronto after that season and dated guys to try and figure it out.”

Bullock came out publicly to Yahoo Sports in 2016, having come out to his family about seven years earlier. The catalyst was former Toronto Maple Leafs general manager and current executive director of the Professional Women's Hockey League Players Association, Brian Burke's son, Brendan. Brendan came out publicly as gay in 2009. “I reached out to Brendan and we quickly became friends. When he came out publicly on TV, I was watching a hockey game and all of a sudden there was someone talking about being gay. It was something I'd never heard before.”

The two young men spoke almost daily and developed a strong friendship. It was a huge relief for Brock, who had no one to talk to about this. “One day he messaged me and said, 'I can't wait for you to come out to your family like I came out to my family.' I ignored him.” It wasn't because he thought his family wouldn't support him, they had already proven that they would. However, Brock's family was also heavily involved in hockey, with his father coaching junior hockey at the time and his brother playing professionally, and Brock feared how their actions would affect him. If he came out to his family, they would be more sensitive to the homophobic nature of the hockey culture at the time and would counter it, which might encourage Brock to come out.

Returning to Brendan's email, Brock delivered a crushing punch to the gut: “Those turned out to be the last things he ever said to me. He died in a car accident two days later.” Brendan died on February 5, 2010. “I felt I needed to honor him in some way,” Brock says. “I decided to tell his family.”

After retiring from the sport in 2010, Brock was coaching players in Sudbury, Ontario. He had kept his secret from those close to him, and though he now lives with his partner, he lived in fear that if his secret was revealed, people would distance themselves from him. “I kept it a secret for about five years, and I thought I was doing a great job.” One day, he got a call from a hockey mom. Brock estimates he's coached about 100 players, so calls from moms were not uncommon.

“All my hockey friends know I'm gay and they choose to work with me, how cool is that?”

But “this time felt different.” His mother called because she wanted to ask Brock out on a date. While trying to think of an excuse, Brock became curious about what type of guy she thought he was and asked the woman's name. The mother replied, “Steve,” and Brock was surprised. In a panic, the mother revealed that her 15-year-old son had told her, that everyone had known for a while. The panic grew. Brock hired someone else. What would happen to them if the coaching business was gone?

“And I thought, 'All my hockey friends know I'm gay and they choose to work with me. How cool is that?'” He then studied the players the way researchers study wild animal behavior. “When they said something homophobic, they froze and apologized. I shrugged and carried on,” he says of the experiment. A culture change seemed to be happening before his eyes.

But he also wondered: Would those same athletes call people f*cks when he wasn't around? When a sprint coach covered the session for him, the answer became clear. At the end of the two-hour workout, the coach had the athletes do 10 more 200-meter sprints. “That's so gay,” the younger athlete reportedly said. He was chided by the older athlete, who ordered him to “do 50 push-ups.” It turned out this was the athletes' way of holding themselves accountable. “All of a sudden, people we didn't know were doing push-ups,” Block says. “One night, another young athlete was on FaceTime with his girlfriend, and she said, 'Let's go out tonight.' He said, 'I can't, I have practice,' and she said, 'That's so gay.' He said, 'Do 50 push-ups or I'm breaking up with you.' And they both sat there and did 50 push-ups.”

A seismic shift was occurring. A few months later, Brock's business was shut down by a major hockey association without explanation. “One night, my dad met with the president of the association and asked him the usual question: 'Is it because Brock is gay?' The president denied knowing, but the hockey mom had told me a few months earlier that everyone knew. The timing was suspicious. I guess the president called some coaches from the team I was volunteering for. When I showed up to the rink the next day for practice, the head coach of the team I'd been working with for about five years removed me from the coaching staff. They did the same to a couple other teams.”

The same summer of 2016, the Pulse shooting happened. The following week, Brock's friend was hosting a charity event in Toronto. He told Brock he'd heard he was on a terrorist hit list. Still, the two decided to go. “We got into an Uber that Friday night and looked at each other like we were going to die tonight.” Security was beefed up, with everyone being searched and scanners galore. Brock and his friend had an undercover security team. Not surprisingly, tensions were running high.

“One day I went to a bar and saw people being strip-searched and I thought, 'Is this really happening?' I got angry and started to wonder when things were going to change. But I started to question myself: when am I going to do something? The next day I called a journalist friend and told him I was coming out.” Bullock became the first openly gay professional ice hockey player.

“I think it's becoming more inclusive.”

Bullock has since become an outspoken advocate. In late 2023 and early 2024, he plans to visit 101 minor hockey teams (1,149 players) in 100 days on his show, “Culture Shift Tours'. Impact Report 95% of players who have been on tour say that they now think more about the importance of being welcoming in their sessions, and almost 97% of coaches say the same. Similarly, 94% say they are more aware of the impact of their words (93% of coaches), and 89% say they are less likely to use offensive language after listening to Bullock.

“It's the best thing I've ever done in my life,” he says, regaining his smile. “It's empowering. I got an email from a mother when I was in Vancouver. One of her son's friends had just finished talking to his team. He told his mother that I might have changed his life. For a 15- or 16-year-old to say something like that. It's unbelievable.” In Calgary, a player told Bullock about an incident that had happened the previous weekend, when other players had thrown his clothes in the shower and placed offensive objects in the mirror for him to see. Although already under investigation, Bullock allowed the player to speak in front of the rest of the team.

“It's funny, in the locker room, everyone talks about girls, video games, and sports. My family knows me even more than that, so in the sessions, we get people to talk about hobbies that they normally wouldn't talk about with their teammates, breaking down conformity. Two of the players said they bake in their free time, and when they heard I was coming back, they baked cookies. So not only did we help this player, but other players completely broke the cultural conformity barrier and brought cookies for a gay man. It makes an impact,” marvels.

In a previous interview, Bullock said he wouldn't encourage queer youth to play hockey for cultural reasons, and sadly, he still holds that belief: “In boys' and youth hockey, yes. I don't think we're there yet. In girls, it's a lot more inclusive, but there's still this question of whether trans people can play.”

The answer is to be more proactive. “If someone says something, we give them a penalty or a suspension. We can teach them about the consequences, and they will probably grow up. I don't think 95% of these people are bad people, maybe even 99%. They don't know any better, and they're part of a culture that's taught this is how to talk, act, dress, walk. They're all totally submissive. Would you know they're football players when you walk into a shop in London?” I reply. “Sometimes,” Bullock nods and continues. “I know I'm a hockey player everywhere I go. When I speak at corporates, I see who used to play hockey. There's too much submissiveness. They're just a product of their environment, and I still don't want to expose queer youth to that kind of environment.”

But there is hope. “I think we're becoming more inclusive,” Bullock opines. “Teenagers today are basically adults. I think the gap is that their words and actions don't align with what they think. In theory they're very inclusive, but they still use language that doesn't align with what they think.” Referring to examples of players refusing to wear Pride jerseys, Bullock says it shows that some think the sport has progressed more than it has. “If you look back to the roots of Pride, it's not what it is now. We still have a long way to go. Having these celebration nights and jerseys when we don't have the right to do it feels like we're going backwards. I don't want false inclusion. We have a long way to go.”