Jim Jeffries was a 330-pound alfalfa farmer who had quit boxing six years earlier when he got a desperate phone call to defend the honor of his race. When he answered the phone, the “Fight of the Century” began.

His mission: to return the world heavyweight championship to a white man, which, of course, included a knockout or two, to the then-champion, Jack Johnson, who was black. Johnson famously became the first black man to win the heavyweight title, defeating Tommy Burns in Sydney, Australia, in 1908, but what upset his critics more than how easily the “Galveston Giant” continued to destroy his opponents was his unwillingness to kowtow or feign humility for the resentful white public.

So began the search for the “Great White Hope,” which ultimately found itself in a fat, ring-rusty Jeffries. A formidable former heavyweight champion in his prime who had defeated Tom Sharkey, Bob Fitzsimmons and James J. Corbett twice each, he retired in 1904 with an unbeaten record. It's unclear how much Jeffries cared about his role as the spokesman for white America, but when he was invited to take part in boxing's first lucrative superfight, he dutifully played the part.“I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that white people are superior to black people,” he declared.

The bout, held on July 4, 1910 in Reno, Nevada, in a venue built just for the event, was as big and meaningful as the 45 rounds it was scheduled to play. Ringside seats sold for $125, the equivalent of more than $4,000 in today's money. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and U.S. President William Howard Taft were called to referee the bout (but both declined). Nine camera crews filmed the crowd of about 20,000 braving 110°F heat. Includes the high foothills of the Eastern Sierra Burns, Sam Langford, Jake Kilrane, and Abe Attell.

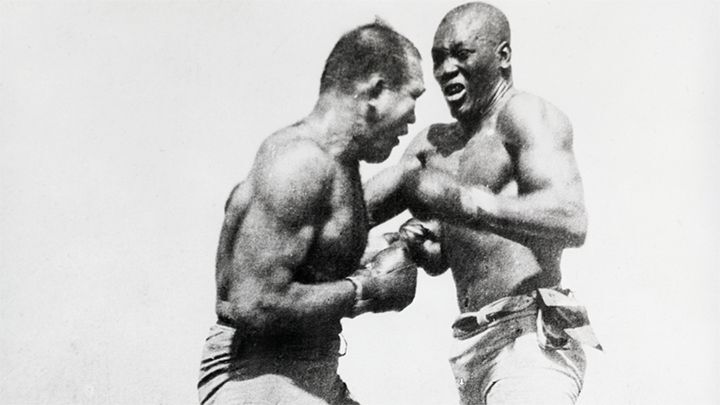

Jeffries, under the direction of his former rival Corbett, managed to slim down to a sturdy 227 pounds in just over eight months for the bout. Bookmakers reported Jeffries as a 10-6 favorite. He looked confident throughout the fight until the bell rang. When Johnson offered Jeffries a handshake in the center of the ring, the former champion declined, but the crowd responded with a roar. It was Jeffries' last accolade.

Now 35 and out of action for years, Jeffries was no match for the more agile and energetic Johnson, who gradually battered the former champion down, leaving him bloody at the mouth and a broken nose. Author Jack London described it as a “hopeless massacre.” At one point, Johnson called to an exhausted Jeffries' corner, where Corbett was lingering: “Mr. Corbett, where do I put him?” For fifteen rounds, Johnson didn't bother to ask, instead putting his opponent down and then down again. It was the former champion's first career knockdown, and prompted Jeffries' corner to throw in the towel. A series of live broadcasts carried the news around the world: Johnson had won. Surrounded by his team as a predominantly white crowd swarmed the ring, the champion once again extended his hand to Jeffries for a handshake.

As one of America's greatest shames, news of the fight's outcome sparked race riots across the country, with dozens of U.S. citizens, mostly black, killed by their own citizens on Independence Day. The wildly popular two-hour film Jeffreys Johnson's World Championship Boxing Bout was banned in many territories. Public opinion of boxing in general soured in some quarters, leading policymakers to push for tougher regulations, and after Johnson lost his title in 1915, it took another 22 years for another black man, Joe Louis, to win it again.

Despite all the anxiety, racial unrest, and legitimate danger surrounding the “Fight of the Century” and its aftermath, one surprising voice put an end to this swelling “controversy.” Years later, when asked to defend the white supremacy narrative one last time, Jeffries admitted, “I could never beat Jack Johnson in his prime. I could never catch him in a thousand years.”