U.S. men’s swimming coach Anthony Nesty initially only swam because his father made him.

“I didn’t enjoy swimming,” he tells TODAY.com in an interview.

“Why he chose swimming, I think, is because of the discipline of the sport,” Nesty adds. “It’s just you and the clock.”

His first swim at 5 in a Learn to Swim program was in the country he grew up in, Suriname, where at the time there was only one 50-meter pool, Nesty says.

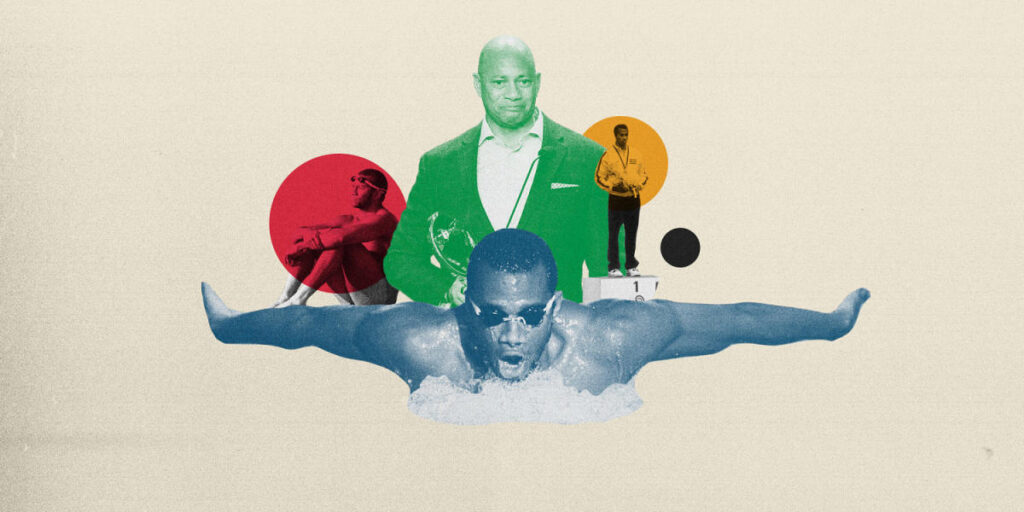

His first swim ultimately turned into USA Swimming tapping him last fall as the head coach for the men’s Olympic team for the 2024 Games in Paris, making him the first Black person to hold a U.S. Olympic swimming head coach position. He previously served as an assistant on the coaching team for the Tokyo Games.

“My dad, he had a vision for me,” Nesty, 56, says.

He says he slowly bought into swimming as his sport early on in his career with each of his wins at local and regional meets across Suriname, the Caribbean and South America.

The butterfly became his specialty, earning him a gold medal for Suriname in the stroke’s 100-meter race at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. The hardware made him the first Black male swimmer to win individual gold, according to Olympics.com. He later swam at the University of Florida on an athletic scholarship, becoming a three-time NCAA champion in the 100-yard butterfly from 1990 to 1992, among other accolades.

Nesty is currently the head men’s and women’s coach at his alma mater, where he has won the SEC Men’s Swim Coach of the Year several times. He won the same award back-to-back in 2023 and 2024 for women’s swimming.

Being a prominent Black coach who often wins in a predominantly white sport is a weight that Nesty takes “seriously,” he told The Associated Press in June 2023.

“You know you’re a role model,” he said. “You have to take that very seriously. Maybe it’s why I work so hard at what I do. I try to be the best Anthony Nesty I can be.”

His ascension into the USA Swimming head coach role is particularly significant given the complicated history of Black people and swimming in the U.S. and the stereotype that they cannot swim. Access to swimming spaces directly correlates to whether Black people swim, Nesty and experts say.

Nesty chats more below about his father, roster building for the Olympics and why there aren’t more Black swimmers in the sport.

Reaching ‘the pinnacle of our sport’

Nesty moved to Florida when he was a teenager to pursue swimming more seriously, he says. He swam at the Bolles School in Jacksonville, and the practice routine there was a wake-up call from his days as a swimmer based in Suriname, he says.

“We used to only train five days a week, Monday through Friday, maybe two hours per practice,” he says. “And then you come to the States, you’re running nine practices, two hours-plus, dry land, weights. For me, I had to get adjusted to that for sure. I was pretty beat up.”

It later became second nature for him, though, as he advanced to collegiate and Olympic competition.

Nesty says his laundry list of accomplishments comes second to his present work, which is his focus.

“I stay busy preparing the athletes. I don’t think of my accomplishments,” he says. “Our sport is demanding for the athletes, the coaches, the families. I want to be the best coach for the University of Florida and of course this summer for us.”

He adds that his late father would be happy to see how far swimming has taken him.

“He put so much time, effort and just financial support — he would be jumping up and down to see that his son is the head coach of the U.S. men’s team,” he says. “That’s kind of the pinnacle of our sport and he would be happy that I’ve reached the top now.”

Nesty spoke with TODAY.com before the recent U.S. swimming trials for athletes to qualify for Paris. But Nesty said in his interview that his goal in building a roster is to win “as many medals as possible.”

“I’m hopeful that when a team is selected, it’s athletes who have a legitimate shot of winning medals,” he said then.

Swimming and ‘a socioeconomic burden’

In recent years, the sport has seen contributions from standout Black swimmers such as Simone Manuel, Lia Neal and Natalie Hinds, to name a few.

“It’s very encouraging,” Nesty says of seeing representation in swimming. “The sport is going to keep growing. … There are a lot of opportunities for all races to get scholarships in our sport.”

There are roughly 335,000 athlete members of USA Swimming, with 2.1% identifying as Black or African American and 62.4% identifying as white, according to a 2023 demographics report issued by the organization. (Another 3.4% of athletes did not respond to the optional ethnicity question.)

Non-athlete members, such as coaches, officials, board members, parents and others who do not swim, total about 42,800, of which 2% are Black or African American and 74.4% are white, the report said. (Another 3.5% of non-athletes did not respond to the optional ethnicity question.)

Nesty says “it’s more of a socioeconomic burden” than ability-based stereotypes that contribute to why there are not as many competitive Black swimmers. Transportation and other logistical demands can be a hurdle, he says.

“It’s also very expensive,” he adds. “And you have to find a pool.”

There are 8.7 million residential inground and above-ground pools as of 2023, P.K. Data, Inc. confirmed to TODAY.com in an email. The company provides market data in the pool and spa industry.

There are 346,500 commercial pool and water spaces as of 2022, the company said.

A 2016 CDC report cited aquatic sector marketing data that indicated there were 309,000 public aquatic venues in the U.S in 2011, but nearly 40% of them were located in five states: Arizona, California, Florida, New York and Texas. Routine inspection reports for 48,632 individual facilities in 2013 found that nearly 80% included data on immediate closure, the report said.

About a third of the country’s public swimming pools remained closed or opened sporadically in 2022 due to a lifeguard shortage and 2023 was estimated to be “as bad … or worse,” according to the American Lifeguard Association in 2023.

TODAY.com has reached out to the CDC for more current data.

Access to public pools and swimming lessons have historically been limited for the Black community.

“The sad legacy is that African Americans were also shut out of swimming lessons, and so they’re much more vulnerable to drowning,” says Victoria W. Wolcott, a history professor at the University at Buffalo whose work includes studying segregation in recreational spaces.

A 2024 CDC report said about 37% of Black adults reported they do not know how to swim, compared to 6.9% of their white counterparts. A 2017 USA Swimming article cited a study that found roughly 64% of African American children have little to no swimming ability, compared to 40% of Caucasian children. The USA Swimming Foundation notes on its website that African Americans ages 5 to 19 are nearly six times more likely to drown in a swimming pool than their Caucasian peers.

‘Ostracized from spaces where there’s water’

The full story behind the disproportionate data dates back to the 1400s, says Ayanna Rakhu, a swim coach whose 2022 doctoral thesis at the University of Minnesota was on the history of Black people and swimming in the U.S.

Voyagers from countries like Portugal and Spain traveled to African countries to observe the people they intended to enslave, Rakhu says.

“What they were seeing is how much we use water as economic development,” she says. “We were the best swimmers, boaters divers, fishers of our time. … Particularly women as divers, diving for clams and shells and money, so what was gold at the time. They would see us transporting things from boat to boat — I’m talking miles of swimming between boats.”

However, Europeans “had no awareness of the water and were not good swimmers,” Rakhu says, so they saw the skill as threatening as they began capturing people.

During U.S. slavery, slave owners engaged in a concerted effort to keep their captives away from the water, Rakhu says.

“Throughout slavery, Africans and African Americans had a strong connection to the water. They used it for bathing and socializing and swimming and exercising, but also to escape from slavery,” Rakhu says. “The message was put into our ancestors’ heads: ‘Stay away from the water. The water is dangerous. We want you away from it so that you can’t use it in the way that you’ve been taught to use it.’ So that’s really where you see, in that 400-year span, the disconnect.”

“We’re still dealing with the repercussions of that time, of being ostracized from spaces where there’s water,” she adds.

One of the biggest challenges is this “trauma” being passed down as “culture,” she says.

“When we say things like, ‘Black people don’t swim,’ we’ve taken that on as culture, when really that’s a part of trauma that exists that has been decontextualized,” she says.

“We don’t know why we have fears or why we don’t want to go near the water. And so when that’s taken out of context, we think, ‘Oh, that’s just culture.’ That’s what we’re able to change. That’s what we have the opportunity to change now, to reclaim that culture,” she adds.

‘The most segregated spaces’

The systematic separation continued post-slavery and during the segregation and Jim Crow eras.

“Swimming in spaces, and this includes swimming pools, beaches, lakes, also ocean beaches as well, those were the most segregated spaces, not just in the South, but nationally in terms of U.S. history,” Wolcott says.

Idlewild, a predominantly Black vacation destination in Michigan beginning in 1912, became an oasis for Black middle-class families to swim and otherwise relax. Black entrepreneurs opened beach resorts elsewhere and made swimming a part of the experience, Wolcott says.

There was a boom in building thousands of public swimming pools and recreation facilities across the country during the 1930s under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The YMCA and the YWCA also had locations across the country.

During the segregated time of the 1930s, Black activists and allies did find a way to swim and teach the next generation. They often negotiated for a day a week at a public white pool, Wolcott says.

“Those were largely segregated, or only open to African Americans briefly throughout the country, despite the fact that Black people, of course, are paying taxes for these facilities,” she says. “So you have situations where, in some cases, swimming pools would be open one day a week for African Americans, that would usually be on Monday, which would be the least-used day. And then ordinarily, what would happen is they would actually drain the swimming pool and refill it before whites went back into this main pool.”

These tactics continued into the 1950s and 1960s, a time period when the Supreme Court ordered public schools to desegregate in the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race.

“Big public high schools would have big swimming pools with swimming lessons, but those were in the white high schools,” Wolcott says. “When you have those public high schools being integrated post-Brown, to the extent that there were efforts to do that, the swimming pools would be closed down because of fears of Black kids being in swimming pools.”

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and to avoid integrated swimming, community leaders and people filled pools with concrete to close them, Wolcott says. The New Deal pools largely closed down as well, she adds. Instead, private pools and their swimming clubs sprung up to “bypass” the Civil Rights Acts, she says.

“Because (it was) a private club, you can practice discrimination,” she says. “They used to be sort of public pools, and then they become these clubs and that’s a way to exclude people.”

The systematic disenfranchisement in this area is the main reason why racial disparities persist in swimming, Wolcott says.

Growing up in Suriname, Nesty says he didn’t encounter unwelcoming experiences during his swimming career. He says he teaches respect and performance as the only acceptable interactions on his teams.

“You have to find a team that welcomes you and can develop you,” he says. “You respect the athletes, your program, the athlete you’re competing against. As human beings, we enjoy high performance. That’s my job as an athlete.”

Making swimming more accessible

There has been a push to make swimming more accessible.

USA Swimming and Total Aquatic Programming have offered workshops to help program, design and build facilities for “community access and financial sustainability, the website says.

Numerous organizations, such as the YMCA, American Red Cross, USA Swimming partner providers, Sankofa Swim International, Black People Will Swim and Black Kids Swim, offer swimming lessons.

Nesty says joining a swimming club will also help people who want to swim competitively.

“You got to start with the basics and club teams across the country, no different than what I did way back when,” he says. “You join the club that’s affiliated with the Learn to Swim program, so it’s very encouraging. Here at Gator Swim Club, they have many kids from all ethnicities competing, coming to practice, which is just awesome to see. The sport is going to keep growing.”

Rakhu is Sankofa’s founder and CEO and says community-based programs work when Black people feel welcomed into the space.

“There’s one thing for something to exist in our neighborhoods. But if we don’t feel invited to it, then when we engage, we need to feel accepted, culturally accepted,” she says.

She also encourages widening the scope of what’s possible for Black people in swimming.

“There’s some room for us to be competitive athletes, but also there’s a lot of room for us to support ourselves and to give back in a more economic way,” she says. “So lifeguards, swim instructors, scuba divers, marine scientists. There is such a niche there for us, given our history as Black people and what our relationship has been with water.”

Remember, Rakhu says: “Swimming is liberation.”

“It’s our healing, our recreation and our occupation,” she adds. “We’re missing out on those three things if we are not adept and understand how to utilize the water to our advantage, which our ancestors once did.”

As for Nesty, he plans to continue his illustrious coaching career in a way where anyone can feel welcome on his teams.

“Whichever team you belong to, you’re going to be welcomed with open arms because the sport is so demanding,” he says. “You have to have empathy for each other. I tell our athletes you got to respect the athlete next to you because you guys are doing the same thing. If you do it as a group, it becomes more palatable. It becomes more fun, and that’s the experience I had as a swimmer. And I would love to hear the athletes of color, when they join a team, sense that they have that camaraderie.”

This article was originally published on TODAY.com