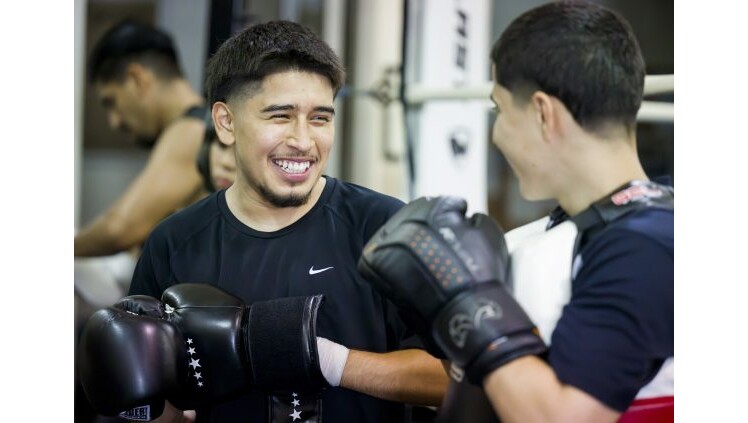

Boxer Diego Aviles (18, left) laughs with boxer Robert Barraza during a break in training at the Anaheim Boxing Club at the Downtown Youth Center in Anaheim on June 7, 2024. (Photo by Leonard Ortiz, Orange County Register/SCNG)

ANAHEIM — If I had met Diego Aviles for the first time anywhere other than a boxing gym, I would have assumed, based on the handshake, that I was meeting a student council member.

Direct eye contact and perfect manners? What young men are expected to adopt during summer job interviews.

I never would have guessed that this good-natured man would regularly beat people up. everyone Someone who had recently appeared before him.

Who would have guessed that a kid who graduated from Magnolia High School in May would also become a national Golden Gloves champion that same month — and, if his coach's research is correct, could become just the second Orange County native to do so?

Few would have guessed that such a humble man, so quick to give credit to others, would be the future contender honored as a rising star at the National Boxing Hall of Fame in April.

He won five national championships between the ages of 15 and 17, and was recently denied the opportunity to compete at the U.S. Olympic Boxing Trials by fate and the fact that he turned 18 two weeks too late as is now required, which is probably not what most would have expected from a soon-to-be professional boxer.

Aviles isn't a big guy, you know? A 5-foot-5, 112-pound young flyweight, he'll be trying out for size (and fun) at 118 pounds in two weeks' time at USA Boxing's National Junior Olympics in Wichita, Kansas, starting June 22.

But watch him spar for 60 seconds and you'll understand: This small, fearsome boxer and puncher could be the next big thing in boxing.

Agile, quick-witted, and confident after nearly 100 fights. At first he lost more than he won, but lately his wins far outweigh his losses. A pressure fighter who doesn't dance or waver. A no-nonsense opponent.

You need not be in a bad temper to attack your opponent, and you need not be overly nervous to execute a beautiful attack.

I just need to focus on boxing.

Game Student

Art James has been Aviles' coach for the past five years. James runs the city of Anaheim's boxing program, currently a nonprofit called Team PunchOut, which plays '80s rock, Bon Jovi and the Cutting Crew. James likens the sport to the old Looney Tunes cartoons with Ralph Wolf and Sam Sheepdog. At the beginning of the episode, the characters punch out, exchange pleasantries and then, well, they beat each other up, right? But then Coyote ends up bandaged up and it's like, 'See you tomorrow, George.' 'See you tomorrow, Sam.' You have to learn to put in the effort, but you also have to learn to let it go.”

I didn't know this yet when I asked Avilés why he got into boxing: “Because it's about hitting people, right?”

Yes, it's true: it's a novelty to be able to hit someone and not have it matter, but what really struck me were the moments of clarity that this sport offers and demands.

“It's a good mental break,” he says. “I see it as kind of therapy, you know? I just go to the gym and let all my emotions out. I think it's good for me to forget myself in the gym.”

Diego has been going to the gym regularly since he was seven years old, initially accompanied by his father to learn self-defence.

Even back then, no one looked at Diego and predicted that he would become a great boxer.

But Diego loved it. He improved his jump rope skills by watching YouTube tutorials. He studied the fights of Mexican star Canelo Alvarez and was inspired. Diego learned there was a lot to learn about the sport, the traps, the strategies. And he loved that part. He never missed a morning run, and he does six to 10 mile endurance training with his teammates, who he says are already struggling to keep up.

When Diego arrived on James' Anaheim canvas as an 11- or 12-year-old, it didn't take the coach with decades of experience long to see something in his new pro. He lost most of his matches, but “they were always close,” James said. “You're playing tough guys in California.”

Antonio Garcia, one of James' older fighters, was quick to recognize that as well.

“I remember he was a small guy and he was just throwing jabs,” Garcia said, “but Art stopped us and said, 'I want you guys to work on your right cross step and throw another jab. Take a step or get an angle.'

“And Diego did it. He was different to the other kids. I thought, 'Wow, cool. This could be something.' … And Art has a lot to do with all of this. Art is incredible. He's a boxing magician.”

James said his boxers have won more than 100 tournaments, including seven national championships, in the 17 years he's been in the city. Among his proud students are Caitlin Orozco, who won the Youth World Championship with Team USA in 2014, and Jonathan Esquivel, who won the U.S. Olympic Trials in 2016.

Now, in addition to teaching classes of 20 novice boxers every Tuesday and Thursday at Anaheim's Downtown Youth Center, James also devotes his time and resources to Aviles and another young boxer, 14-year-old phenom Lupita Ruiz, a soon-to-be student at Garden Grove-Santiago High School who has never lost in 35 bouts. This friendly girl is truly fearsome.

She's a lot like Aviles, James and Garcia say, because she's serious, coachable and loves the sport. It helps that Aviles is there to mentor her.

“He hits hard, he knocks people down and he puts on a show,” Lewis said, “and he's such a hard worker. It's amazing the way he works. He pushes me to run more, run faster, throw more punches. He's a real motivator for me.”

Battle on Top

Next week, James, his players and their families will stay in Airbnbs, which are cheaper than hotels, hoping to catch a connecting Southwest flight to Wichita on time. They'll eat food prepared by their coach, like plates of broccoli with lemon, fingerling fish or store-bought roasted chicken without the skin.

They focus for days on the fight, chewing gum before the bout to strengthen their jaws, and keeping their eyes on their opponent and the weight gain (a little easier for Aviles, who's six pounds heavier this time around). Of course, there's a championship on the line and, at the end, another prize: pizza.

Now, in August, Aviles plans to take the next step.

“I'm going to take him pro,” James said. “Winning a Golden Gloves is a big thing. He's now up there with Sugar Ray Leonard, Tommy Hearns and Muhammad Ali. To win is a big deal. So he's not going to stay an amateur because he's watching all the kids he knows go pro.”

Not only did Aviles win the prestigious title, how He's won the best boxing matches of his life so far, including a crushing semifinal victory over 20-year-old Jordan Roach, who was the top seed in his weight class at the U.S. Olympic Trials late last year.

It was as if the fight had slowed down, Aviles told me. “It was a beautiful fight,” James said.

“It was just different,” Aviles said. “I felt better, I had more power, I had more speed. And I was a little bit overconfident. You know what? I was a little bit overconfident. I had my hands down a little bit. It was crazy because I had my hands down and (Roach) was like, 'Hey, put your hands up!' And I don't know why I did it, but I did it.”

As it turns out, there's more to this fighter than it even realizes.