In the summer of 2003, a silent killer stalks the cobblestone streets of Paris.

A massive heatwave has swept over France since August 4, with temperatures rising more than 20 degrees Fahrenheit above normal for nine consecutive days. By the end of the outbreak, France had recorded around 15,000 deaths, more than expected at the time, many of them elderly and in Paris. No one checked on them until it was too late.

For heat researchers like Christy Ebi, a professor of global health at the University of Washington, the event provided a new understanding of how dangerous heatwaves are in a world warmed by climate change.

“A lot of people died because it was so big. That's when it got attention,” Ebi said.

All eyes will be on the lighting of the Olympic torch and the weather forecast on Friday, July 26th. Paris will host the Summer Olympics 21 years after a deadly heat wave occurred on the same day in 2003. Due to continued global warming, the Olympic Village is not equipped with air conditioning, increasing the possibility of a heat wave at the Olympics. . Some Olympic teams have expressed concern about the situation.

Many Parisians leave Paris with strategies to cope with the August heat. Typically, the city feels quiet in early August as people seek beaches and coastal climate.

This year, the city will be filled with around 10,500 players and staff, 20,000 journalists and 31,500 volunteers. Millions of people attend the Olympics as spectators.

Experts say a heatwave during the Games could put athletes and spectators at serious risk. Last summer was a stark example of this concern. The Cerberus heat wave caused temperatures in southern Europe to rise to 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

Ollie Jay, a professor of thermal science at Australia's University of Sydney, said if a similar heatwave were to hit during the Olympics, “it could be a huge problem” and warned of the potential heat exposure for Australian athletes. He also gave advice on how to deal with the situation. . Jay helped create the International Olympic Committee's consensus standards for how to protect athletes from extreme heat at the Olympics.

The International Olympic Committee said in a statement: “The health and well-being of our athletes is always at the center of our concerns. The IOC takes heat concerns very seriously. The Paris 2024 Organizing Committee is committed to supporting the IOC and the international In consultation with sports federations, we have taken a wide range of measures to reduce the impact of the temperatures that may occur this summer.''The Paris 2024 organization, which is responsible for coordinating the Games, said in response to questions about the heat of the Games. There wasn't.

Some researchers question whether the Olympics should continue to be held in the middle of summer, even if measures are taken to combat the heat.

“If you're really focused on keeping your athletes healthy and giving their best performance at the Olympics, if you hold it in July in a mid-latitude city like Paris, that's not going to happen. ” said Associate Professor Jennifer Banos. Arizona State University School of Sustainability.

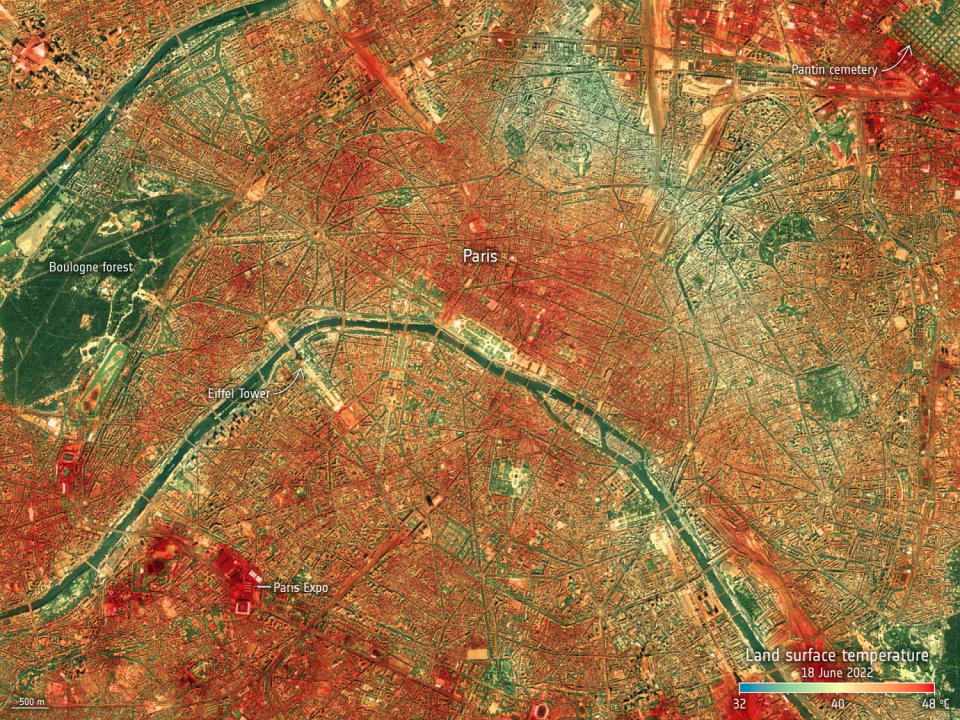

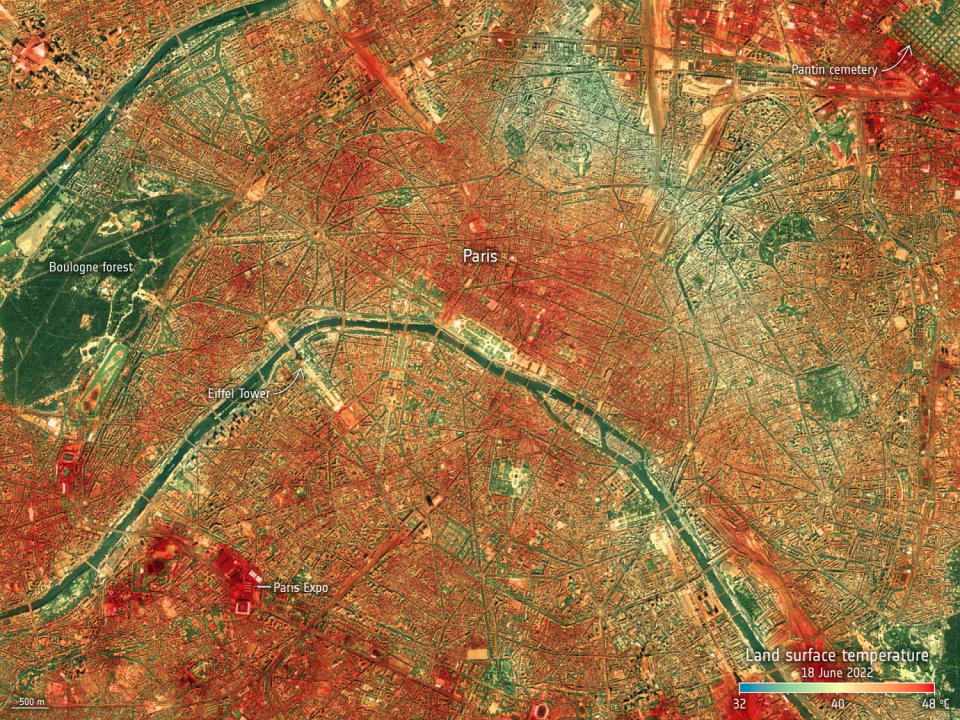

Paris is particularly susceptible to heatwaves. Paris has only 10% of public green space, many of its building roofs are made of heat-trapping zinc, and as of 2020, only 25% of French homes had air conditioning.

The city traps heat and is noticeably hotter than its surroundings, suffering from what researchers call the urban heat island effect. Temperatures are about 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than in surrounding rural areas, but can reach 15 degrees Fahrenheit in hot spots, according to a 2014 report from the city's Department of Urban Planning.

“This is the highest risk of any European capital,” said Pierre Macero, a statistician at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who assessed heat exposure concerns in 854 European cities.

The Olympic Village in Paris will have a wildlife-friendly rooftop, carbon-friendly building materials and green spaces including a public park.

However, as part of a plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the tournament, the village will not install air conditioning in the players' rooms.

Instead, the complex relies on natural airflow cooling and groundwater cooling systems. Organizers told The Associated Press last year that even during a heat wave, nighttime temperatures would never rise above 79 degrees.

The climate is warmer than in 2003. A study in Nature Climate and Atmospheric Science suggests that heatwave temperatures could now be up to 7°F warmer than during the 2003 heatwave.

At the last Summer Olympics in Tokyo, the heat pushed dozens of athletes over the edge, forcing organizers to reschedule the competition.

About 110 athletes suffered heatstroke during the Tokyo Games as temperatures at some outdoor venues exceeded 95 degrees Fahrenheit, according to a study published in the journal BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. There were 10 patients suffering from severe heat stroke, including heat stroke. According to the magazine's article, several athletes required ice bath treatment.

Concerned about rising temperatures in the Tokyo metropolitan area, Olympic organizers moved endurance events such as the marathon and race walking to Sapporo, about 500 miles north, and adjusted their start times to earlier in the morning. It didn't work. Runners in the women's marathon faced track temperatures of over 100 degrees and high humidity.

Almost half of the heat-related illnesses occurred at the Sapporo endurance event.

The Tokyo Games were held a year late under a state of emergency declared due to the new coronavirus infection, with no spectators in attendance, which eased the burden on emergency personnel. Shota Tanaka, a part-time researcher at Kokushikan University and a former medical operations manager at Olympic venues, said the absence of spectators had dramatically eased the burden on medical staff, but it was an issue that Paris must address.

The number of heatstroke patients was “expected to be very high,” Tanaka said. “Holding the Olympics from August is a fundamentally crazy idea from a heatstroke perspective.”

Athletes prepare for the heat in the weeks leading up to the tournament.

Franck Brochery, a senior researcher in exercise and environmental physiology at the French Institute of Sport, will advise his country's athletes on climate acclimatization before the competition, with athletes exercising for an hour each day in a heated chamber set at ambient temperature. He said he would encourage them to do so. The temperature is about 95 degrees. Brochery said most athletes will likely need to train for about two weeks before the competition to prepare for the toll the heat will have on their bodies.

“If you're not acclimated, you don't have a chance to perform on the day of the event,” Brochery said, adding that there is no downside to acclimatization.

Vanoss, an associate professor at Arizona State University and a former collegiate distance runner, said heat can severely limit an athlete's performance even when acclimatized.

“I don't think many records will be broken,” Vanos said of the Paris endurance event.

Heat-preparation experts said athletes will have an easier time preparing for the heat than spectators and volunteers who don't have the athletes' level of fitness or acclimatization.

Brochery said Paris organizers and hospitals needed to plan for heatstroke among spectators.

The amateur marathon will start at 9 p.m., and the short distance race will start at 11:30 p.m. Measures are taken to reduce heat risk during late hours.

“It's not normal to organize a big recreational marathon in the summer,” Vanos said. “What Paris is doing could be quite dangerous for the average recreational runner.”

Brochery said the course is hilly and demanding.

“People will face problems during the race,” he said. “Increasing the burden on the health care system is a real problem and a risk.”

NBCUniversal owns the U.S. broadcast rights to the 2024 Olympics.

This article originally appeared on NBCNews.com