Chris Viotti left the old Golden Eagles' locker room and staggered onto the Salt Palace floor.

John Stockton. Jerry Sloan. Karl Malone. They all stood there before the morning gunfight. So Biotti did something most 20-year-olds could only dream of. That's when he started hitting shots with future NBA Hall of Famers.

A few months ago, Biot was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, playing hockey at Harvard University. Now, the Calgary Flames' first-round draft pick was rubbing elbows with some of the NBA's biggest names in Salt Lake City.

“Life couldn't get any better than this,'' he thought.

“We had a great relationship with the Jazz players at the time,” Biot said.

“If they went to a Jazz game, I think they became fans of ours,” said former Eagles center Rick Barkovic.

That was in 1988, when the Jazz and Golden Eagles shared the same roof. That winter, the city was fascinated by what was happening in the Salt Palace. The Jazz advanced to the NBA playoffs. The Golden Eagles won the International Hockey League. The palace was abuzz every night as each team packed in for days.

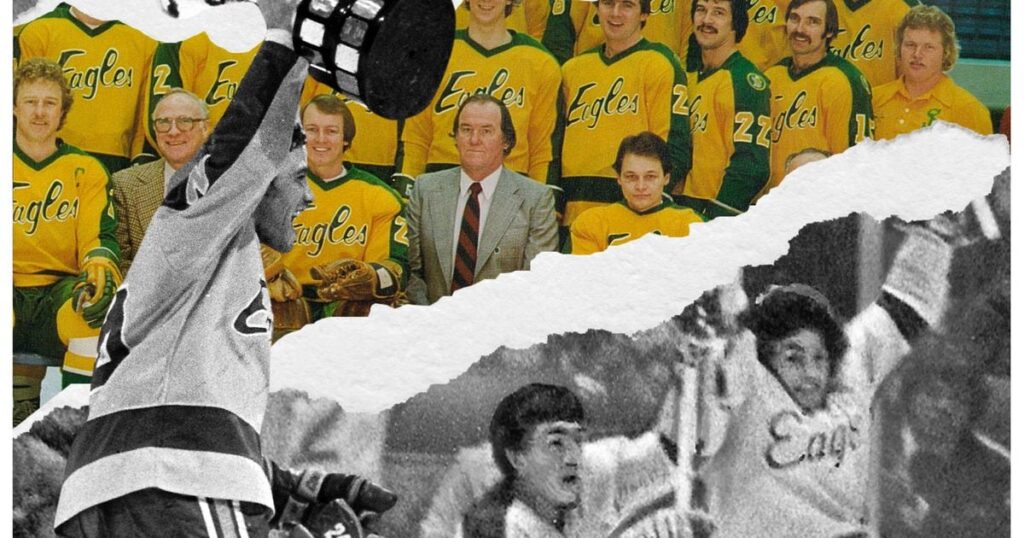

(Brian Acord) Salt Lake Golden Eagles star Lyle Bradley celebrates at the Salt Palace on May 5, 1975.

“Salt Lake was magical,” Biot recalled.

Nearly 40 years later, hockey and basketball will once again share the same roof in Utah with the impending move of the Arizona Coyotes to Salt Lake City. The Golden Eagles want you to know that Utah hockey history started with them. Their stories are littered with drunken brawls, travel troubles, and even murder. But on the ice, they won big. And in the 1988 season, the Jazz and Golden Eagles were the hottest tickets in town.

“We were outsmarting the basketball team,” former owner Bill Accord said. “I'm telling you, we broke the fire code. We're going to add seats in the concourse so people can get in.”

inside story

As the Golden Eagles waited to take off and return home from a grueling 17-day expedition, their plane taxied down Kansas City's runaway streets for what felt like ages.

Team owners Bill Acord and Art Teese, who were sitting at the front of the plane, had no idea what was causing the delay until their manager made an unusual request.

“One of our guys came in here…and he was like, 'Oh my god,'” Accord recalled. “And he said, 'I hate to ask this, but could you just eat half your sandwich?'

Accord stared blankly. “What are you listening to?”

(Brian Acord) During a Salt Lake Golden Eagles game in April 1975, opposing players get into an altercation with fans at the Salt Palace.

The manager went on to explain the unfortunate situation. Before they left for the airport, he was making sandwiches and packing them in boxes. On the way, the bus somehow ran over the box. The players in the back were threatening to mutiny if they didn't get food quickly. Rationing became necessary.

Accord gave food away to greedy players. The manager promised it would never happen again, but we all knew it would (at least in some way). Dysfunction was the law of minor league hockey at the time, especially for the Eagles, who had a more checkered and mysterious history than any other team.

The Golden Eagles began in the 1960s when Dan Meyer purchased the team and moved it to Salt Lake. They were the only professional show in town. The Jazz did not arrive from New Orleans until 1979.

Financial conditions were difficult from the beginning. The misfortune came to a dramatic end in 1972 when Meyer attended an NHL-WHL meeting in Minnesota. Meyer told assistant general manager and coach Al Robbins that he was heading to his room. Fifteen minutes later, he was dead on the ground beneath a 19th-floor window at the Radisson South Hotel.

Initially it was ruled a suicide, but after investigating, police said they were not certain. “There was an open wallet, empty money, glasses with broken lenses on the bathroom floor, keys in the room, and blood stains on the floor and walls,” police said in a statement.

Years later, Golden Eagles players and coaches still talk about that day.

“They saw him jump out the window,” Accord said. “And the window was fixed and couldn't be opened…he was renting it.” [money] From the wrong people. ”

(Salt Lake Tribune) Thursday, December 28, 1989 The print page features images and stories from Golden Eagles hockey games.

After Meyer's death, the team nearly folded until Charlie Finley, who owned the NHL's California Golden Seals and Oakland Athletics, kept it afloat for a short time. Thane Accord and Teeth purchased it from him.

The Accords previously owned a team in Utah. The local ABA basketball team, the Utah Stars, was theirs. But the world of sports ownership was still new.

The Accord reminded me of the first time I pulled up to an owners meeting. He was using an old pickup truck. One of the other minority owners suggested that they rent a limousine and that once the starters were announced, the owners would be announced in the spotlight right after.

“I remember sitting there and being like, 'Are you ashamed of me?'” he said. “I think I'll be late for the game.”

But there was a bigger problem.

Thane Acord was murdered in a robbery in 1980. An 18-year-old boy named John Calhoun forced Mr. Acord to withdraw $800 from his bank account, then tied him and his wife, Lorraine, in the basement of his home. He shot both at close range.

The Salt Palace was renamed the Accord Arena. The governor spoke at the wake.

“I couldn't deal with it,” said son Bill Accord. “…I had to take over everything.”

Said Doug Palazzari, a 1980 player and future NHL center.that [wasn’t] secret.But it was never a problem [on the team]. My sons took over and did a great job. ”

The franchise had been in a state of instability for years, but its move to the International Hockey League gave it a second life.

How to build a championship

The 1988 championship season began at an air force base, where players donned jumpsuits and stared at fighter jets.

The team's preseason poster was Top Gun-themed and was endorsed by a group of minor league warriors and NHL prospects.

“It was pretty cool,” Biot said. “They were putting it up in bars all over town.”

(Brian Acord) Salt Lake Golden Eagles enforcer Randy Turnbull, 4, battles an opposing player on the ice during a 1987 game.

This team was different than years past. The Golden Eagles became the primary affiliate of the Calgary Flames. That means all players were either drafted or released by NHL teams.

In the past, the Golden Eagles' roster has been a mixed bag of talent as the team has bounced back and forth between affiliations. Now, Salt Lake was a high-level NHL feeder system.

Their coach, Paul Baxter, played for the Pittsburgh Penguins and Flames. The player acquired an old Suburban from a local booster. A steam room was installed in the salt palace for recovery.

“Belonging to the Flames, you’re talking first class,” Barkovic said.

However, in the early stages, the team's performance did not match expectations. And after starting below .500, Baxter sat in the locker room before the game with a children's book in hand. “A small engine that can do it” I have it in my hand.

He read every page with deadly seriousness to the professional hockey player in front of him.

“I think I can do it, and I know I can do it,” Boitte said, reenacting a line from the book. “Then he stood up and said, 'Gentlemen, I know we can do it.'

They won 40 games in the regular season and the fans loved it.

Previously, players could sneak out at 1 p.m. and ski Brighton with Snowbird for $9. As the team got better and more fans filled the Salt Palace, people started recognizing them.

“One owner came to us and said, 'Hey, you guys were seen skiing,' and that's a violation of your contract,” Boitte recalled. “We never did it again.”

Instead, it began trading tickets for free rounds of golf at Park City courses.

The Golden Eagles had become a nightly favorite. On the ice, the players were hit so hard that opponents literally jumped into the stands.

“The boards were really forgiving,” said Stu Grimson, who eventually played in the NHL.

It became common for spectators to pour beer on opposing players if a player nearly fell into a fan's lap. There was no plexiglass between the ice and the seats. One player was so frustrated that he put on his skates and chased a fan 10 rows into the cement stands, commentator Mike Ballack recalled.

On the ice, the antics between players and fans were a sight to behold.

The Golden Eagles held a men's and women's bikini contest during their menstrual vacation. Media members voted for the winner.

(Brian Acord) Salt Lake Golden Eagles fan favorite Doug “Pizza” Palazzari hoists the trophy.

The individuality of the players shined throughout the season. There was a player named Barkley Plager, who later became a defenseman for the St. Louis Blues, and he was often ejected from games for hard hits. He used the break to take players' dentures out of their lockers and put them in luggage to be shipped back to Salt Lake. By the end of the game they were gone.

“There were guys who tried to get him kicked out with him so he wouldn't be alone in the locker room,” Brian Accord said. “The players had no teeth so they ate soup for the rest of the road trip.”

By the end of that season, the team was so good that it could barely practice. Baxter made it into a game. He selected a specific number of minutes for the team to practice, and the team placed his bet on his remarks for $12 a side.

“He would say, 'Today we're going to practice for 41 minutes,'” Boitte said. “And we'll all cheer. I don't think he knew about the bet.”

The weather became warmer and the playoffs became more difficult. During one series in Dallas, the rink box continued to fog up due to the Texas heat. The match was postponed several times. Radio calls were made from a wooden platform above the goal, which required a spiral staircase to reach.

“It's just minor league hockey,” Brian Accord said.

However, the Golden Eagles easily made it through the playoffs that year after an early seven-game scare for the Peoria Rivermen. They defeated the Colorado team in six games and scored nine goals in the Turner Cup final against Flint Spears.

Thousands of people greeted him at the airport gate with trophies.

hockey return

The Golden Eagles were eventually sold to Jazz owner Larry H. Miller and then acquired by Detroit owners. The team is now defunct. But former goaltender Paul Skidmore still receives an envelope in the mail every year containing a hockey card.

It usually comes from Salt Lake fans trying to collect autographs for all the players.

Even after all this time, the Golden Eagles' legacy still carries weight.

And now Utah fans are preparing for a new team to come together.

This NHL team won't have the same drama. It won't stay at the Red Roof Inn in Flint, Michigan, and it won't be grounded in Peoria, Illinois because the plane's wheels literally froze on the tarmac (all true stories).

But it's going to be big-time hockey.

And no one should forget who broke the ice in Salt Lake City.