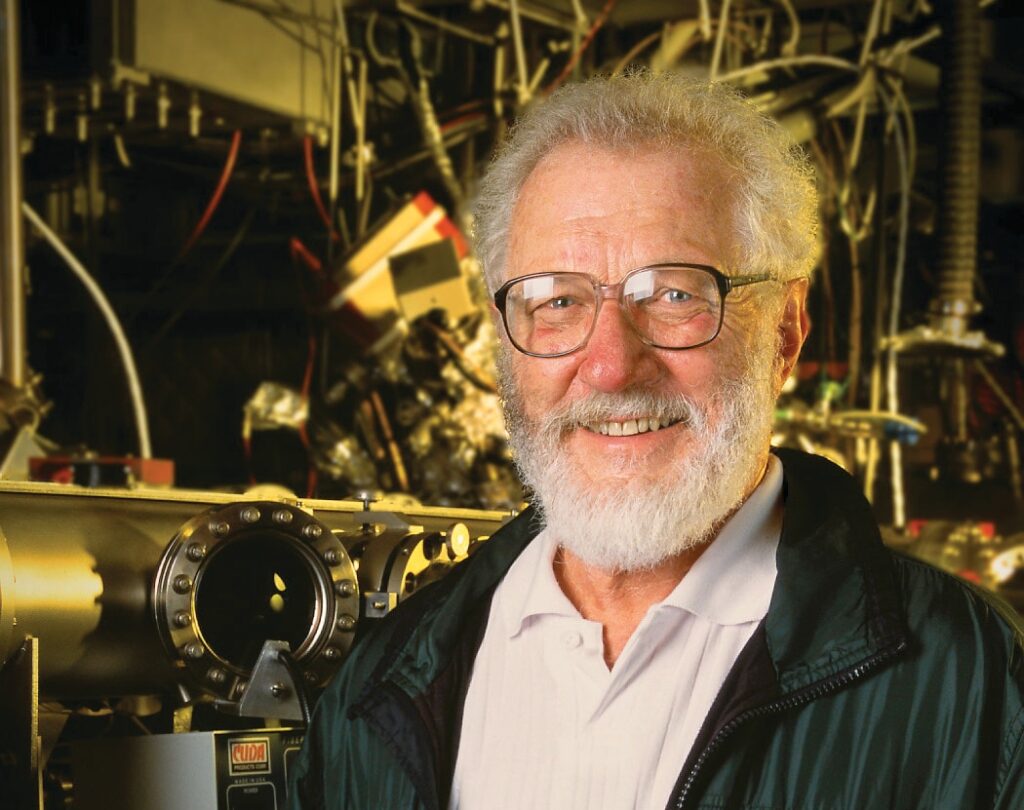

A German-born researcher with a thick white beard and a strong skepticism toward scientific authority, Dr. Kromer is responsible for the development of semiconductor heterostructures, stacked devices that are the basis of advanced lasers and high-speed transistors. won a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2000. .

He shared half of the prize money with Russian physicist Djores Alferov. Zhores Alferov worked independently and in parallel on the development of the device. The other half went to Jack Kilby, a Texas Instruments researcher who played a central role in the invention of the integrated circuit, or microchip.

The Nobel Committee said their work “laid the stable foundations of modern information technology.”

Dr. Kromer began his scientific career in laboratories in West Germany and the United States in the mid-1950s, shortly after the transistor was invented. This device replaced vacuum tubes as electronic switches and amplifiers, ushering in the development of modern electronics. Although typically constructed from a single material, usually silicon, Dr. Kromer proposed using a type of sandwich structure, or heterostructure, made of different materials to create faster transistors. did.

In 1963, he applied his heterostructure research to lasers. Lasers, which had only been invented three years earlier, could only operate at low temperatures and short pulses. Dr. Cromer developed a way around these problems and devised the basic principles of a device known as a double-heterostructure laser, which became the basis for the first commercial semiconductor laser.

His colleague John Bowers, director of the Energy Efficiency Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said in a eulogy that the device “was used around the world in fiber-optic networks that made the Internet possible and transformed the world.” Ta.

“It was a question of making possible something that would simply not be possible without heterostructures,” Cromer told the New York Times after winning the Nobel Prize. Without this structure, he added, “there would be no CD players or CDs,” along with LED lights and countless other electronic devices.

Dr. Cromer started out as a theoretical physicist. His first employer, a communications laboratory run by the German Postal Service, insisted that he stay away from research equipment for fear of breaking something. And he said, when he developed this idea, he said: Regarding heterostructure lasers, he was only interested in the basic science behind the concept.

“I didn't really care about the application,” he told IEEE Spectrum, the flagship journal of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

But his bosses at Silicon Valley research firm Varian Associates refused to grant him the resources to develop the technology, “because there was no practical application for this device,” he said. I recalled this in a lecture. Other researchers, including Alferov, continued to build and refine the first heterostructure lasers.

“This was actually a classic case of judging a fundamentally new technology, rather than judging it by what new applications it could be put to. createBut it just depends on what can be done with existing applications,” Cromer said in his talk, calling on institutions to focus less on what cutting-edge science “serves.” .

“This problem is as old and pervasive as the technology itself,” he added, noting that double-heterostructure lasers are “just one example in a long chain of similar examples.” It won't be the last either. ”

Herbert Kramer was born in Weimar, Germany, on August 25, 1928, the eldest of three sons. His father was a civil servant and his mother a housewife. They had no high school education and were not very interested in science. Still, they sought to encourage Dr. Cromer's natural affinity for mathematics, physics, and chemistry, including purchasing some 20 volumes of encyclopedias for him.

During World War II, as a teenager looking for additional reading material, Dr. Cromer went to the library twice a week and worked his way through the science section, gaining “the realization that we could derive from a small set of very fundamental laws.'' ” fascinated me. That's a very far-reaching conclusion,” he said in the oral history.

After graduating from high school in 1947, he entered the University of Jena, where he studied under the physicist Friedrich Hund during the post-war Soviet occupation. As social conditions became increasingly repressive, attendance at lectures declined. Some of his more liberal classmates disappeared without explanation.

“I had no idea whether they had fled to the West or ended up in the German branch of Stalin's concentration camps,” he recalled in his autobiographical essay.

In the summer of 1948, while working for Siemens in Berlin, Dr. Kramer decided to resettle in West Germany and secured a seat on a return flight on the Berlin Airlift. He enrolled at the University of Göttingen and received his doctorate in physics in 1952, writing a thesis on the “hot electron” effect in transistors.

Dr. Cromer conducted some of his early heterostructure research at the RCA Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey, and settled in California in 1959, joining Varian Associates in Palo Alto. He moved there with his wife, Marie Louise, and their young children, including their 2-year-old daughter Sabine, who drowned in a pool shortly after arriving, according to a report in the local Peninsula Times Tribune.

His wife passed away in 2016. Information about the survivors was not immediately available, but IEEE Spectrum said the survivors had five children.

Dr. Cromer joined the faculty at the University of Colorado in 1968 and moved to the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1976, ultimately holding joint positions in the electrical and computer engineering department and the materials department. He received one of the German government's highest honors, the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit, in his 2001 year, and the following year he was awarded the IEEE Medal of Honor.

After winning the Nobel Prize, Dr. Cromer received a surge of attention, which he mostly tried to ignore. “I get a lot of invitations that are clearly there for decoration. I usually say no,” he told an interviewer at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “But he has one invitation that I think I can give back to society, and that's an invitation to speak to students,” he said, speaking to students in elementary and high schools.

“Society has been good to me, and this is one way I can repay it,” he said.